MozartrazoM

Quirino Gasparini’s Rediscovered Masterpieces Take the Stage in Bern and Basel

On December 14th and 15th, a significant event in music history will unfold as the Camerata Rousseau, under the direction of Leonardo Muzii, presents previously unperformed works by Quirino Gasparini.

A Historic Moment for Music

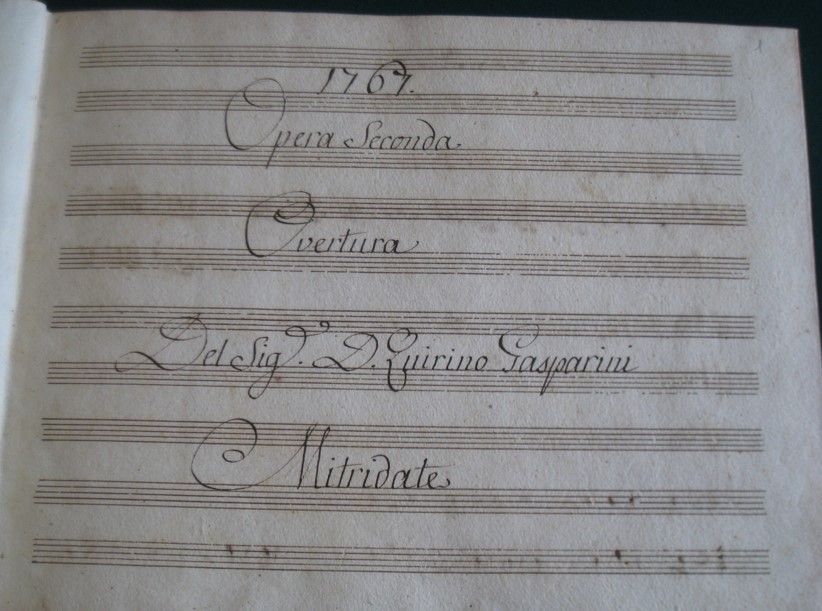

These concerts in Bern and Basel mark the world premiere of the aria Al destin che la minaccia from Gasparini’s Mitridate, re di Ponto (1767), which was famously plagiarized by Mozart in his own version of Mitridate.

These performances are an opportunity to reassess Gasparini’s influence on 18th-century music and uncover the legacy of a composer whose work has often been overshadowed by others. The program also features a concerto for harpsichord in F major by Gasparini, alongside compositions by Josef Mysliveček, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, and Joseph Haydn.

Bologna Connections

Quirino Gasparini’s rediscovered Mitridate aria takes centre stage in Bern and Basel, shedding light on Mozart’s reliance on this forgotten composer.

"Without Gasparini, there would be no Mozart Mitridate. The evidence lies in the manuscripts—and in the music itself."

@MozartrazoM

The Camerata Rousseau’s upcoming concerts in Bern and Basel mark the historic world premiere of Quirino Gasparini’s Al destin che la minaccia, an aria from his 1767 opera Mitridate, re di Ponto. Overshadowed by Mozart’s later adaptation, Gasparini’s work demonstrates its profound influence on the young composer, whose manuscripts reveal direct borrowings. These performances highlight Gasparini’s overlooked genius and invite a re-evaluation of his pivotal role in 18th-century music.

Quirino Gasparini: Bergamo’s Forgotten Genius

Born in Gandino, near Bergamo, in 1721, Gasparini was trained in Milan and Bologna, where he studied with the renowned Padre Martini. His career included operatic successes and significant contributions to sacred music. As maestro di cappella of Turin Cathedral from 1760 until his death in 1778, Gasparini composed prolifically, producing works such as the groundbreaking Mitridate, re di Ponto. This opera, performed in Turin in 1767, served as the direct model for Mozart’s version just three years later.

Despite his remarkable output—including over 17 masses, numerous litanies, and a substantial corpus of instrumental works—Gasparini remains relatively unknown outside academic circles. However, his influence is undeniable: even pieces attributed to Mozart, such as Adoramus te, were later identified as Gasparini’s compositions.

Mozart and Mysliveček Under Gasparini’s Shadow

The concerts highlight Gasparini’s pivotal role in shaping the music of both Mozart and Mysliveček. At just 14 years old, Mozart, under the guidance of his father Leopold, drew heavily from Gasparini’s Mitridate when composing his own. Manuscript evidence reveals direct borrowing—not only from the structure and themes of Gasparini’s arias and recitatives but also from his orchestral innovations.

Similarly, Mysliveček’s Nitteti, performed in Bologna in 1770, borrows stylistically and thematically from Gasparini’s Mitridate. Both composers’ reliance on Gasparini underscores his central position in the musical networks of Turin, Bologna, and Milan during this period.

The Rediscovery of Gasparini

These performances mark a critical step in restoring Gasparini’s rightful place in music history. While Mozart’s Mitridate continues to enjoy frequent performances, Gasparini’s original has been neglected. The Camerata Rousseau’s commitment to historical accuracy and rediscovery offers audiences a rare glimpse into the artistry of a composer whose work inspired some of the greatest names in classical music.

Program Details

Saturday, December 14, 2024 | 7:30 PM | Bern

Grosse Saal, Konservatorium

Sunday, December 15, 2024 | 5:00 PM | Basel

Don Bosco

Performers:

- Anastasiia Petrova, Soprano

- Diego Ares, Harpsichord

- Camerata Rousseau on period instruments

- Conductor: Leonardo Muzii

Program:

- Josef Mysliveček: Symphony in B-flat major

- Quirino Gasparini: Harpsichord Concerto in F major

- Quirino Gasparini: Aria Al destin che la minaccia from Mitridate, re di Ponto

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Aria Voi avete un cor fedele

- Joseph Haydn: Symphony No. 44 (“Trauersinfonie”)

You May Also Like

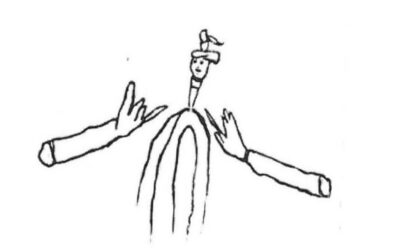

Unveiling the Truth Behind the Drawing

H. S. Brockmeyer’s latest research unravels the mystery behind a July 5, 1791, letter from Mozart to his wife. This remarkable investigation uncovers the original, unembellished drawing Mozart included—vastly different from the altered version widely reproduced in collections today. The discovery raises significant questions about historical accuracy and the intentional shaping of Mozart’s legacy.

The Deceptive Nature of Mozart’s Catalogue

The Thematic Catalogue traditionally credited to Mozart is fraught with inaccuracies, suggesting that many of his famous works might not be his at all. This prompts a necessary reevaluation of Mozart’s legacy and the authenticity of his compositions.

The Mozart Myth Unveiled: A Deeper Look

Mozart’s legacy is far from the untarnished narrative of genius that history would have us believe. The web of deceit woven around his name by those closest to him, including his own widow, reveals a much darker story.

The Other Side of Mozart’s Legacy

Explore the untold story of Mozart, where myth and reality collide. Our critical examination of his life and works reveals a legacy shaped by profit, myth-making, and misattribution. Join us in uncovering the truth behind the man and his music.

The Deception Surrounding Mozart’s Legacy

Anton Eberl’s confrontation with Constanze in 1798 exposed a web of deceit surrounding Mozart’s legacy, revealing that several of his compositions were falsely attributed to the late composer. This chapter uncovers the ethical dilemmas and controversies that have marred the posthumous reputation of one of history’s most celebrated musicians.

Leopold’s Invisible Hand

Behind the glittering performances of young Wolfgang and Nannerl Mozart lay the meticulous guidance of their father, Leopold. Often considered a mere teacher, Leopold’s role in composing and shaping their early musical successes has been largely overlooked. Was the child prodigy truly a genius, or was it Leopold who orchestrated his son’s rise to fame?