Constanze Mozart’s Enduring Love

Myths, Misconceptions, and Mysterious Graves

Although some have doubted her devotion, Constanze’s own words and actions illustrate a widow deeply committed to preserving Mozart’s legacy. Diaries, personal correspondence, and eyewitness testimony all challenge the notion that she neglected his memory—while the circumstances around his burial grow ever more perplexing.

“He was of so sweet a disposition altogether that it was impossible to argue with him…”

Constanze

In H. S. Brockmeyer’s latest analysis, the widely debated affection of Constanze Mozart for her first husband, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, is re-examined through letters, visitors’ accounts, and a host of little-known historical records. Critics have often accused Constanze of neglecting Mozart’s memory by failing to erect a proper headstone for him, yet, as Brockmeyer highlights, her day-to-day actions speak volumes about her loyalty and her heartbreak.

Constanze’s diary entry of 11 August 1829, lovingly referencing Mozart’s fortepiano—where he reportedly composed the Zauberflöte, La Clemenza di Tito, the Requiem, and a Freemason Cantata—demonstrates her lifelong attachment. Despite the hardships and misunderstandings in their marriage, she cherished this instrument, eventually sending it to her eldest son, Karl. Moreover, she traveled with a treasured painting of Mozart, by her brother-in-law Joseph Lange, safeguarded in a custom-made wooden case. The English musician and publisher Vincent Novello, along with his wife Mary, visited Constanze in 1829 and confirmed her unwavering devotion. As Mary wrote in her journal, Constanze proudly displayed the painting, the famous inkstand permanently stained with Mozart’s ink, and even locks of his hair—a sentimental gesture that leaves little doubt about her profound feelings.

One of the many overlooked details, Brockmeyer points out, is the monumental gravestone currently crowning the final resting place of Constanze’s second husband, Georg Nissen, in Salzburg’s St. Sebastian Church cemetery. Today, the name MOZART gleams in gold on that shared stone, an homage to Constanze’s first husband that endures for centuries—an act entirely consistent with a woman who would not allow her beloved to be forgotten. Yet the research also calls attention to the contradictions regarding Leopold Mozart’s grave, which ended up in a communal burial site rather than near the grand Nissen headstone. The confusion, incomplete records, and repeated renovations contribute to a sense of unresolved mystery surrounding the family’s final resting places.

In parallel, the controversy about Mozart’s alleged grave at St. Marx in Vienna adds an extra dimension of intrigue. Scholars, tourists, and enthusiasts have paid homage to a cenotaph believed to mark the spot where Mozart might lie, but the revelations unearthed by H. S. Brockmeyer indicate that there is no definitive proof of the composer’s remains in that location. In fact, subsequent attempts to verify whether bones found in Salzburg could be those of Mozart or his relatives—particularly the 2004 and 2005 forensic investigations—ended with inconclusive DNA results. The same is true of the famed skull, purported to be Mozart’s, which has yet to be verified scientifically and remains in the care of the Mozarteum Foundation.

Particularly fascinating are the shadowy details surrounding Mozart’s final days: the contradictions in eyewitness testimony about who visited him, the confusion regarding a simple or third-class funeral, and the complete lack of the grand commemorations that one might expect for a composer whose music so electrified Vienna. By contrast, the city of Prague honored Mozart with an elaborate memorial service on 14 December 1791, while Vienna seemingly carried on without public ceremonies—an oversight that continues to puzzle historians.

Brockmeyer also introduces an astonishing story that places Mozart’s corpse in the Freihaus Theater of his friend and collaborator Emanuel Schikaneder, who staged The Magic Flute. An eyewitness account suggests that the composer’s body was briefly laid out there, although official records remain silent on the matter. This bizarre episode dovetails with the enduring rumor that Mozart’s physical remains simply vanished from public sight. According to local anecdotes, neither the Church nor the authorities possessed clear or consistent documentation as to where or how he was buried.

By interweaving testimony from Constanze, Sophie Haibl (Constanze’s sister), the Novellos, and forensic experts centuries later, Brockmeyer paints a picture of a widow doing all in her power to safeguard the memory of “her inexpressibly beloved husband,” in the face of church procedures, royal edicts, and myriad forces beyond her control. This first installment of H. S. Brockmeyer’s comprehensive study peels back layer after layer of myth and speculation—revealing a steadfast love that contradicts long-held assumptions about Constanze’s indifference.

Stay tuned for Part II, in which H. S. Brockmeyer delves even further into the convoluted archives, possible political and ecclesiastical motivations, and the broader historical context that shaped Mozart’s fate and legacy. How did Austria’s Catholic Church and the imperial authorities handle such a high-profile death? And why were so many of Vienna’s influential Freemason brothers conspicuously silent at Mozart’s funeral? The journey into this enigma continues.

You May Also Like

#4 The Golden Spur

While often portrayed as a prestigious award, the Golden Spur (Speron d’Oro) granted to Mozart in 1770 was far from a reflection of his musical genius. In this article, we delve into the true story behind this now-forgotten honour, its loss of value, and the role of Leopold Mozart’s ambitions in securing it.

Mozart Unmasked: The Untold Story of His Italian Years

Explore the lesser-known side of Wolfgang Amadé Mozart’s early years in Italy. ‘Mozart in Italy’ unveils the complexities, controversies, and hidden truths behind his formative experiences, guided by meticulous research and rare historical documents. Delve into a story that challenges the traditional narrative and offers a fresh perspective on one of history’s most enigmatic composers.

Another Example of Borrowed Genius

The myth of Mozart’s genius continues to collapse under the weight of his reliance on others’ ideas, with Leopold orchestrating his son’s supposed early brilliance.

A Genius or a Patchwork?

The genius of Mozart had yet to bloom, despite the anecdotes passed down to us. These concertos were not the work of a prodigy, but a collaborative effort between father and son, built on the music of others.

Myth, Reality, and the Hand of Martini

Mozart handed over Martini’s Antiphon, not his own, avoiding what could have been an embarrassing failure. The young prodigy had a lot to learn, and much of what followed was myth-making at its finest.

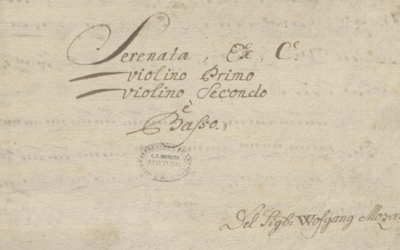

Mozart’s Serenade? A New Discovery? Really?

In Leipzig, what was thought to be a new autograph of Mozart turned out to be a questionable copy. Why are such rushed attributions so common for Mozart, and why is it so hard to correct them when proven false?