Wolfgang Amadé Mozart

From Innsbruck to Bolzano: A Journey of Ambition and Networking

From Innsbruck to Bolzano, the Mozart family’s journey was a blend of strategic networking and missed opportunities, revealing the challenges of securing fame in 18th-century Europe.

Mozart in Italy: The Untold Story

Was Mozart truly a solitary genius, or was he merely the instrument of his father’s ambition? “Mozart in Italy” challenges the conventional narrative, revealing a complex dynamic between father and son that shaped the course of music history. Prepare to question everything you thought you knew.

“In Bolzano, no public performance opportunities were offered to Wolfgang, and the city’s lack of musical enthusiasm led Leopold to cut their stay short, moving on to seek better prospects elsewhere”

Mozart in Italy

The Mozart family’s journey through Europe in the late 18th century was not just a physical voyage but a carefully orchestrated campaign to secure opportunities and establish Wolfgang’s reputation as a musical prodigy. Their travels from Innsbruck to Bolzano reveal the challenges and strategic maneuvers employed by Leopold Mozart to ensure his son’s success.

The Innsbruck Encounter

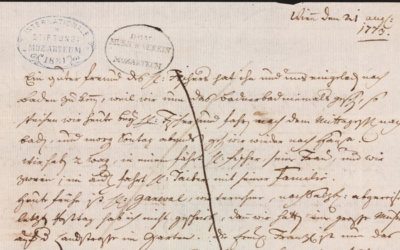

On Friday, December 15, 1769, Leopold and Wolfgang Mozart arrived in Innsbruck, where they were welcomed with a level of hospitality that Leopold would later emphasize in his correspondence. Their stay at the Alla Croce Bianca Inn set the tone for the carefully planned social interactions that would follow. Leopold’s first act upon arrival was to write to his wife, updating her on their journey and ensuring that the lines of communication remained open—an essential practice in an era when letters were the only means of staying connected with loved ones.

Leopold’s correspondence was marked by a keen awareness of how it might be read by others, including potential censors, which led him to maintain a measured tone, often highlighting only positive events. This careful self-presentation was crucial in his efforts to cultivate the image of Wolfgang as a rising star in the European musical landscape.

The next day, the Mozarts were hosted by Count Johann Nepomuk Spaur, who provided them with a carriage and extended several invitations to social gatherings. These meetings were more than mere social calls; they were opportunities for Leopold to network and for Wolfgang to perform, even if only informally, thereby reinforcing their connections with influential figures in the region.

The Stopover in Bolzano

After a series of well-received visits and performances in Innsbruck, Leopold and Wolfgang continued their journey, arriving in Bolzano on December 21, 1769. However, the reception in Bolzano was markedly different from the warm welcome they had received in Innsbruck. Despite being hosted by notable local figures such as Johann Anton Kurzweil and Joseph Kaspar Anton von Gumer, the Mozarts found little opportunity to perform publicly. This lack of engagement was disappointing, as Bolzano, despite its connections to the aristocracy and the Freemasons, did not provide the vibrant musical environment Leopold had hoped for.

Leopold’s frustration with Bolzano’s lack of musical opportunities is evident in his letters, where he describes their stay as brief and unremarkable. The city, still under Habsburg control, offered no concerts or significant public performances for Wolfgang, leading Leopold to decide to move on sooner than planned.

The Role of Freemasonry

Throughout their travels, Leopold skillfully leveraged the networks of Freemasonry to open doors that might otherwise have remained closed. In Bolzano, the connections facilitated by the Masonic networks provided introductions to influential families and secured the Mozarts’ passage through Italy. These relationships were crucial, as they offered hospitality and provided letters of recommendation that would be valuable in the Italian cities they had yet to visit.

However, the absence of musical enthusiasm in Bolzano made it clear that not every stop on their journey would be fruitful. The Mozarts’ experiences in these early stages of their Italian journey highlight the unpredictable nature of 18th-century travel, where success depended as much on social connections as on talent and ambition.

You May Also Like

The Violin Concertos: Mozart’s Borrowed Genius

Mozart’s violin concertos are often celebrated as masterpieces, but how much of the music is truly his? This article delves into the complexities behind the compositions and challenges the authenticity of some of his most famous works, revealing a story of influence, imitation, and misattribution.

#2 The Hidden Truth of Mozart’s Education

In this video, we uncover the hidden truth behind Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s early education and challenge the long-held belief in his effortless genius. While history often celebrates Mozart as a child prodigy, effortlessly composing music from a young age, the reality is far more complex.

The London Notebook

The London Notebook exposes the limitations of young Mozart’s compositional skills and questions the myth of his early genius. His simplistic pieces, fraught with errors, reveal a child still grappling with fundamental musical concepts.

The Mozart Question

In this revealing interview, we delve into the lesser-known aspects of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s life, challenging the long-standing myth of his genius. A Swedish journalist explores how Mozart’s legacy has been shaped and manipulated over time, shedding light on the crucial role played by his father, Leopold, in crafting the career of the famed composer.

Georg Nissen and the Missing Notebooks

After Mozart's death, his widow, Constanze, found a steadfast partner in Georg Nikolaus von Nissen, a Danish diplomat who dedicated his life to preserving the composer's legacy. Nissen not only compiled an extensive biography of Mozart but also uncovered and...

Letters Under Surveillance

In a world without privacy, Leopold Mozart’s letters were carefully crafted not just to inform but to manipulate perceptions. His correspondence reveals a calculated effort to elevate his family’s status while avoiding any mention of failure or controversy.