K.143

A Recitative and Aria in the Shadows of Doubt

Ergo interest, Quaere superna—a Latin recitative and aria in G major, supposedly by the young Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. It is catalogued as K.143 (73a), but its attribution is fraught with uncertainties that would make even the staunchest Mozart devotee hesitate. This “work” is a case study in how musicology has built entire legends on quicksand, blithely ignoring gaping holes in the narrative.

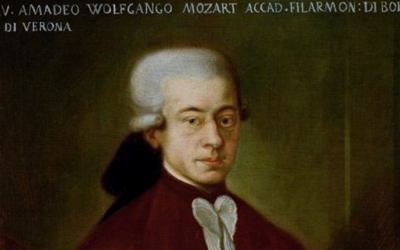

Mozart in Italy: The Untold Story

Was Mozart truly a solitary genius, or was he merely the instrument of his father’s ambition? “Mozart in Italy” challenges the conventional narrative, revealing a complex dynamic between father and son that shaped the course of music history. Prepare to question everything you thought you knew.

“Sometimes, the most convincing attribution is simply the one no one dares to question.”

Mozart in Italy

A Patchwork of Guesses

The sole surviving manuscript, housed in the Library of Congress, is attributed to Mozart with more hope than evidence. Key details are conspicuously absent: no date, no clear author, no definitive instrumentation. Even the watermark of the manuscript, often a vital clue for authentication, has vanished. Adding to the enigma, there are no other copies or printed editions, and the identity of the text’s author is unknown.

Yet, the piece was included in the first Köchel catalogue with a speculative date: Salzburg or Milan, 1772–1773. This guesswork has since ossified into “fact” for many scholars. But here’s the kicker: the manuscript is a so-called “fair copy,” combining the handwriting of both Wolfgang and Leopold Mozart. The pristine condition of the manuscript screams preparation for presentation, not original composition. Are we really to believe that this uninspired recitative and aria were the work of the teenage prodigy at the height of his creative vigor?

The “Gentle Melodic Contours” of… Someone Else?

Advocates for Mozart’s authorship point to a letter Leopold Mozart wrote in Milan on February 3, 1770, where he mentions two motets composed by Wolfgang for castrati. However, the stylistic features of K.143 reveal nothing uniquely Mozartian. Instead, the music adheres rigidly to the Italian church style of the period, showing “hardly any individual traits.” This blandness alone should raise eyebrows. Could this be a rushed transcription of another composer’s work? The suggestion, while plausible, has been curiously dismissed without serious consideration.

Some argue that Mozart’s copies of sacred works often served pedagogical purposes. But K.143 lacks the depth or ingenuity to justify such an effort. Why would a budding genius waste time copying an uninspired motet? The piece neither challenges compositional norms nor offers any discernible expressive innovation.

The Elephant in the Room

What if K.143 isn’t Mozart’s at all? This hypothesis—likely the most straightforward explanation—has been conveniently ignored. Why? Because it challenges the sacrosanct image of Mozart as a prodigious composer, churning out masterpieces at every turn. Yet the evidence (or lack thereof) makes a compelling case: K.143 is probably a sloppy patchwork cobbled together by Leopold, using Wolfgang’s handwriting to pass it off as the son’s work. This would not be the first time Leopold blurred the lines of authorship to advance his son’s career.

The refusal to entertain this possibility exposes the bias entrenched in Mozart scholarship. Instead of grappling with the uncomfortable uncertainties surrounding K.143, musicologists have leaned on circular reasoning and vague stylistic comparisons to maintain its place in Mozart’s oeuvre.

A Final Note of Dissonance

K.143 serves as a stark reminder of how little we truly know about Mozart’s catalog. If this uninspired piece can be so confidently attributed to him without solid evidence, how many other “Mozartian” works are similarly dubious? Perhaps it is time to admit that the emperor—or in this case, the child prodigy—might not always have been wearing any clothes.

You May Also Like

The Violin Concertos: Mozart’s Borrowed Genius

Mozart’s violin concertos are often celebrated as masterpieces, but how much of the music is truly his? This article delves into the complexities behind the compositions and challenges the authenticity of some of his most famous works, revealing a story of influence, imitation, and misattribution.

#2 The Hidden Truth of Mozart’s Education

In this video, we uncover the hidden truth behind Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s early education and challenge the long-held belief in his effortless genius. While history often celebrates Mozart as a child prodigy, effortlessly composing music from a young age, the reality is far more complex.

The London Notebook

The London Notebook exposes the limitations of young Mozart’s compositional skills and questions the myth of his early genius. His simplistic pieces, fraught with errors, reveal a child still grappling with fundamental musical concepts.

The Mozart Question

In this revealing interview, we delve into the lesser-known aspects of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s life, challenging the long-standing myth of his genius. A Swedish journalist explores how Mozart’s legacy has been shaped and manipulated over time, shedding light on the crucial role played by his father, Leopold, in crafting the career of the famed composer.

Georg Nissen and the Missing Notebooks

After Mozart's death, his widow, Constanze, found a steadfast partner in Georg Nikolaus von Nissen, a Danish diplomat who dedicated his life to preserving the composer's legacy. Nissen not only compiled an extensive biography of Mozart but also uncovered and...

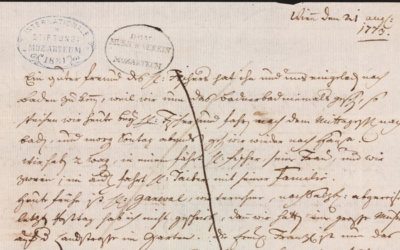

Letters Under Surveillance

In a world without privacy, Leopold Mozart’s letters were carefully crafted not just to inform but to manipulate perceptions. His correspondence reveals a calculated effort to elevate his family’s status while avoiding any mention of failure or controversy.