Leopold Mozart’s Literary Theft

The Forgotten Scandal Behind the Poem at the Mozarteum

Hidden within the Mozarteum’s archives lies a poem that has long been hailed as a tribute to the young Mozart children. But behind this innocent façade is a story of deception, literary theft, and one father’s ambition to rewrite history.

Mozart: The Fall of the Gods

This book offers a fresh and critical look at the life of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, challenging the myths that have surrounded him for centuries. We strip away the romanticised image of the “natural genius” and delve into the contradictions within Mozart’s extensive biographies. Backed by nearly 2,000 meticulously sourced citations, this work invites readers to explore a deeper, more complex understanding of Mozart. Perfect for those who wish to question the traditional narrative, this biography is a must-read for serious music lovers and historians.

"Leopold Mozart turned a tribute to French musicians into false praise for his own children, altering the legacy of both."

@MozartrazoM

When we think of the Mozart family, it’s easy to imagine a picture of prodigious musical talent nurtured by the guidance of a loving father. Leopold Mozart has long been seen as a proud patriarch, tirelessly promoting his children’s gifts to the courts of Europe. However, there’s a lesser-known story that reveals a much darker side of his ambition—a tale of literary theft that has been hidden for centuries.

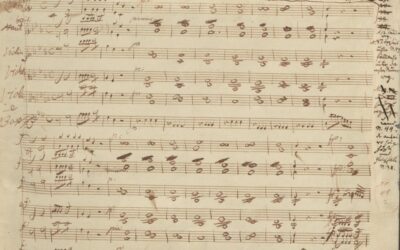

At the Mozarteum in Salzburg, there is a poem that has been preserved for posterity. Titled “Sur les enfants de Mr. Mozart”, it appears to be a tribute to the musical talents of young Wolfgang and Nannerl, composed by an anonymous French poet in 1764. For years, scholars, biographers, and music lovers have accepted the poem as a legitimate celebration of the Mozart children’s talents. But as with so much of Mozart’s history, the truth is far more complicated.

The poem, which was copied by Leopold Mozart himself and stored at the Mozarteum, is in fact a forgery. Or more accurately, it is a stolen work, altered to suit Leopold’s purposes. The original poem, written by Barnabé Farmian Durosoy, had nothing to do with the Mozarts. It was actually composed to honour a group of celebrated French musicians. Leopold, however, had other plans for it.

The Deception

Rather than celebrating Nannerl and Wolfgang, the poem was written in praise of French artists such as Claude Balbâtre, Pierre Gaviniés, Jean-Baptiste Duport, and Jean-Pierre Guignon—musicians who were highly regarded in France at the time.

Leopold saw an opportunity. He copied the poem but removed the names of the French musicians, replacing them with references to his own children. In doing so, he transformed the text into a lavish tribute to Wolfgang and Nannerl, making it seem as though these young prodigies were worthy of admiration even from the gods themselves. Leopold went as far as to alter the pronouns in the poem, shifting the focus from “them”—the French musicians—to “you,” directly addressing his own children.

The result was a manipulated text that appeared to be a high-minded celebration of the Mozart family’s musical brilliance. To anyone unfamiliar with the original poem, the altered version would have seemed legitimate. Leopold’s clever edits effectively erased the true subjects of the poem, allowing his children to bask in the borrowed glory of France’s musical elite.

A Critical Eye

The deception went undetected for years. No one at the time thought to question the poem’s authenticity, and it wasn’t until the late 19th century that doubts began to emerge. Edmond de Guerle, a French literary critic writing for the Revue chrétienne in 1873, was among the first to call the poem’s origins into question. Guerle noted the irregularities in the poem’s metre and rhyme scheme, pointing out that the sequence of rhymes didn’t match typical French poetic conventions. He criticised the poem, calling it the work of an “inexperienced poet justly unknown.”

What Guerle didn’t know, however, was that the poem wasn’t simply the product of a bad poet—it had been altered by Leopold Mozart himself. The text had been lifted from Durosoy’s Les sens, a poem in six songs, with entire sections cut and edited to fit Leopold’s agenda. In the process, the poem lost its rhythm and structure, creating the inconsistencies that Guerle had noticed.

The Unmasking of Leopold’s Theft

It wasn’t until the advent of the internet that the true origin of the poem became widely accessible. Today, a quick search reveals the original poem by Durosoy in the French National Library (BnF). Copies of Les sens can now be viewed online, where it becomes immediately obvious that Leopold Mozart copied the text, beginning from the middle to make it more difficult to trace the source.

However, the damage had already been done. For centuries, the poem had been accepted as a legitimate tribute to the Mozart children, with Leopold’s version enshrined in the Mozarteum archives. It had even been included in Constanze Mozart’s biography of Wolfgang, further embedding it into the narrative of the Mozart family’s exceptionalism.

Conclusion: A Legacy of Deception

Leopold Mozart’s literary theft is just one example of the lengths to which he went to secure his children’s place in history. But it also serves as a reminder that the history we inherit is often more complex than we think. Behind the myths and the legends, there are hidden stories of ambition, manipulation, and deception.

As we continue to challenge the established narratives around Mozart, it’s important to look beyond the surface and question the sources that have shaped his legacy. Only then can we uncover the true story behind one of history’s most famous musical families.

You May Also Like

Rediscovering Musical Roots: The World Premiere of Gasparini and Mysliveček

This December, history will come alive as the Camerata Rousseau unveils forgotten treasures by Quirino Gasparini and Josef Mysliveček. These premieres not only celebrate their artistry but also reveal the untold influence of Gasparini on Mozart’s Mitridate re di Ponto. A pivotal event for anyone passionate about rediscovering music history.

The Curious Case of Mozart’s Phantom Sonata

In a striking case of artistic misattribution, the Musikwissenschaft has rediscovered Mozart through a portrait, attributing a dubious composition to him based solely on a score’s presence. One has to wonder: is this music really Mozart’s, or just a figment of our collective imagination?

The Illusion of Canonic Mastery

This post explores the simplistic nature of Mozart’s Kyrie K.89, revealing the truth behind his early canonic compositions and their implications on his perceived genius.

The Unveiling of Symphony K.16

The Symphony No. 1 in E-flat major, K.16, attributed to young Wolfgang Mozart, reveals the complex truth behind his early compositions. Far from the prodigious work of an eight-year-old, it is instead a product of substantial parental intervention and musical simplification.

The Cibavit eos and Mozart’s Deceptive Legacy

The Cibavit eos serves as a striking reminder that Mozart’s legacy may be built on shaky foundations, questioning the very essence of his so-called genius.

K.143: A Recitative and Aria in the Shadows of Doubt

K.143 is a prime example of how Mozart scholarship has turned uncertainty into myth. With no definitive evidence of authorship, date, or purpose, this uninspired recitative and aria in G major likely originated elsewhere. Is it time to admit this is not Mozart’s work at all?