Mozart’s German Mask

Mozart, the Anschluss, and Nazi Propaganda

After the 1938 Anschluss and Hitler’s entrance into Vienna, the Nazis seized upon Mozart’s legacy, portraying him as the embodiment of Germanic identity and cultural superiority. Adolph Meuer, writing for the Signale für die musikalische Welt, claimed that the unification of Austria and Germany was inspired by Mozart himself, who, according to Nazi rhetoric, expressed his ‘adamantine German voice’ in his music and suffered when he was abroad. The 1941 Mozartwoche des deutschen Reiches further intensified these efforts, led by figures like Alfred Weidemann and musicologists of the regime, who aimed to align Mozart with the greatest German composers. The celebrations cloaked in ‘international’ allure were, in truth, tools of propaganda, reinforcing Nazi ideals while suppressing foreign influence. This appropriation distorted Mozart’s legacy, painting him as a symbol of racial purity and nationalistic pride.

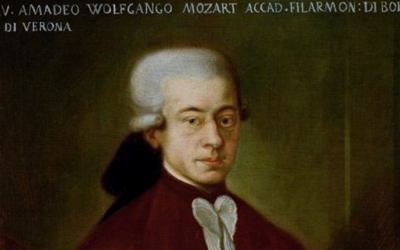

Mozart: The Fall of the Gods

This book compiles the results of our studies on 18th-century music and Mozart, who has been revered for over two centuries as a deity. We dismantle the baseless cult of Mozart and strip away the clichés that falsely present him as a natural genius, revealing the contradictions in conventional biographies. In this work, divided into two parts, we identify and critically analyze several contradictory points in the vast Mozart bibliography. Each of the nearly 2,000 citations is meticulously sourced, allowing readers to verify the findings. This critical biography of Mozart emerges from these premises, addressing the numerous doubts raised by researchers.

"The Salzburg Festival became a platform for Nazi propaganda, distorting Mozart’s legacy to fit their nationalistic and racial agenda."

Mozart: The Fall of the Gods

The Nazi Appropriation of Mozart

In 1938, following the Anschluss and Hitler’s triumphant entry into Vienna, Nazi propaganda found a perfect symbol in Mozart to justify their political aims. Adolph Meuer, writing for Signale für die musikalische Welt (The Musical World Gazette), proclaimed that the union of Austria and Germany had been inspired by Mozart himself. According to Meuer, the Salzburg Festival, now finally “international,” would honour the greatest of musicians, one who, “speaking purely German in music,” felt “fiercely German,” so much so that he suffered when abroad and “prayed daily to honour himself and the entire German nation.” Thanks to Mozart, Germany’s national forces had reunited, and Austria had at last reconciled with its motherland.

Reinventing Mozart’s Identity

To prove Mozart was truly German, despite Salzburg in the mid-18th century being neither Austrian nor German but an independent principality, the Nazis had to dig up late 19th-century arguments. In preparation for the 1941 celebrations, they emphasised similarities between Mozart and the greatest German composers. The task was personally handled by writer and director Alfred Weidemann (1916-2000), who, in a small booklet, revived an old thesis by musicologist Ludwig Nohl, detailing the influence of Mozart on Wagner.

The 1941 Mozart Week and Nazi Ideology

Exactly 150 years after Mozart’s death, the commemorative book for the Mozartwoche des deutschen Reiches (German Reich’s Mozart Week) in 1941, co-authored by Schenk, Schiedermair, and Orel, celebrated the Germanic spirit of Mozart’s work. It highlighted the Germanic qualities of the composer and glorified the superiority of German art. That same year, Joseph Goebbels attended a performance of The Marriage of Figaro at the Berlin Opera, noting in his diary his annoyance at the excessive presence of Jews in the audience.

A Façade of Respectability

The Nazis cloaked the celebratory concerts held in Germany and the occupied territories in a façade of respectability, but their intention remained to elevate compatriots and undermine foreigners. While Damisch led the Wiener Mozart-Gemeinde, he also presided over the German Reich’s Mozart Week, where, under his control, regime musicologists like Schiedermair, Haas, Müller von Asow, Gregor, Orel, Engel, Steglich, and Valentin delivered lectures.

Racism and Propaganda

The Mozartwoche was governed by racist criteria. The speeches by Baldur von Schirach and propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels during the Mozart celebrations bear witness to their disdain for foreigners. The supposed “international” aspect of these events was a mere illusion. Outwardly, they presented a cultured, peaceful image, while Hitler and his generals constantly contemplated war, and thousands of Jews were being incinerated in crematoriums.

Musicology and Nazi Ideals

The SS were tasked not only with protecting the Nazi elite and exterminating those deemed “racially and biologically inferior,” but also with advancing the study of race. Heinrich Himmler funded Joseph Müller-Blattau’s musicological studies on Aryan music, tracing it to folk traditions, and Karl Gustav Fellerer’s efforts to demonstrate the Germanic roots of Gregorian chant with substantial financial backing.

The Lasting Legacy of Nazi Musicology

An authoritative legacy from these “research” efforts was Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart, conceived during the Nazi era. It remained recommended reading during our university days. Friedrich Blume, then editor-in-chief, continued his role unchallenged until 1968, writing further “essential” contributions to modern musicology on Mozart and the “Viennese classicism.”

You May Also Like

#2 The Hidden Truth of Mozart’s Education

In this video, we uncover the hidden truth behind Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s early education and challenge the long-held belief in his effortless genius. While history often celebrates Mozart as a child prodigy, effortlessly composing music from a young age, the reality is far more complex.

The London Notebook

The London Notebook exposes the limitations of young Mozart’s compositional skills and questions the myth of his early genius. His simplistic pieces, fraught with errors, reveal a child still grappling with fundamental musical concepts.

The Mozart Question

In this revealing interview, we delve into the lesser-known aspects of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s life, challenging the long-standing myth of his genius. A Swedish journalist explores how Mozart’s legacy has been shaped and manipulated over time, shedding light on the crucial role played by his father, Leopold, in crafting the career of the famed composer.

Georg Nissen and the Missing Notebooks

After Mozart's death, his widow, Constanze, found a steadfast partner in Georg Nikolaus von Nissen, a Danish diplomat who dedicated his life to preserving the composer's legacy. Nissen not only compiled an extensive biography of Mozart but also uncovered and...

Letters Under Surveillance

In a world without privacy, Leopold Mozart’s letters were carefully crafted not just to inform but to manipulate perceptions. His correspondence reveals a calculated effort to elevate his family’s status while avoiding any mention of failure or controversy.

#3 Leopold Mozart’s Literary Theft

Hidden within the Mozarteum’s archives lies a poem that has long been hailed as a tribute to the young Mozart children. But behind this innocent façade is a story of deception, literary theft, and one father’s ambition to rewrite history.