Mozart’s German Mask

Mozart, the Anschluss, and Nazi Propaganda

After the 1938 Anschluss and Hitler’s entrance into Vienna, the Nazis seized upon Mozart’s legacy, portraying him as the embodiment of Germanic identity and cultural superiority. Adolph Meuer, writing for the Signale für die musikalische Welt, claimed that the unification of Austria and Germany was inspired by Mozart himself, who, according to Nazi rhetoric, expressed his ‘adamantine German voice’ in his music and suffered when he was abroad. The 1941 Mozartwoche des deutschen Reiches further intensified these efforts, led by figures like Alfred Weidemann and musicologists of the regime, who aimed to align Mozart with the greatest German composers. The celebrations cloaked in ‘international’ allure were, in truth, tools of propaganda, reinforcing Nazi ideals while suppressing foreign influence. This appropriation distorted Mozart’s legacy, painting him as a symbol of racial purity and nationalistic pride.

Mozart: The Fall of the Gods

This book compiles the results of our studies on 18th-century music and Mozart, who has been revered for over two centuries as a deity. We dismantle the baseless cult of Mozart and strip away the clichés that falsely present him as a natural genius, revealing the contradictions in conventional biographies. In this work, divided into two parts, we identify and critically analyze several contradictory points in the vast Mozart bibliography. Each of the nearly 2,000 citations is meticulously sourced, allowing readers to verify the findings. This critical biography of Mozart emerges from these premises, addressing the numerous doubts raised by researchers.

"The Salzburg Festival became a platform for Nazi propaganda, distorting Mozart’s legacy to fit their nationalistic and racial agenda."

Mozart: The Fall of the Gods

The Nazi Appropriation of Mozart

In 1938, following the Anschluss and Hitler’s triumphant entry into Vienna, Nazi propaganda found a perfect symbol in Mozart to justify their political aims. Adolph Meuer, writing for Signale für die musikalische Welt (The Musical World Gazette), proclaimed that the union of Austria and Germany had been inspired by Mozart himself. According to Meuer, the Salzburg Festival, now finally “international,” would honour the greatest of musicians, one who, “speaking purely German in music,” felt “fiercely German,” so much so that he suffered when abroad and “prayed daily to honour himself and the entire German nation.” Thanks to Mozart, Germany’s national forces had reunited, and Austria had at last reconciled with its motherland.

Reinventing Mozart’s Identity

To prove Mozart was truly German, despite Salzburg in the mid-18th century being neither Austrian nor German but an independent principality, the Nazis had to dig up late 19th-century arguments. In preparation for the 1941 celebrations, they emphasised similarities between Mozart and the greatest German composers. The task was personally handled by writer and director Alfred Weidemann (1916-2000), who, in a small booklet, revived an old thesis by musicologist Ludwig Nohl, detailing the influence of Mozart on Wagner.

The 1941 Mozart Week and Nazi Ideology

Exactly 150 years after Mozart’s death, the commemorative book for the Mozartwoche des deutschen Reiches (German Reich’s Mozart Week) in 1941, co-authored by Schenk, Schiedermair, and Orel, celebrated the Germanic spirit of Mozart’s work. It highlighted the Germanic qualities of the composer and glorified the superiority of German art. That same year, Joseph Goebbels attended a performance of The Marriage of Figaro at the Berlin Opera, noting in his diary his annoyance at the excessive presence of Jews in the audience.

A Façade of Respectability

The Nazis cloaked the celebratory concerts held in Germany and the occupied territories in a façade of respectability, but their intention remained to elevate compatriots and undermine foreigners. While Damisch led the Wiener Mozart-Gemeinde, he also presided over the German Reich’s Mozart Week, where, under his control, regime musicologists like Schiedermair, Haas, Müller von Asow, Gregor, Orel, Engel, Steglich, and Valentin delivered lectures.

Racism and Propaganda

The Mozartwoche was governed by racist criteria. The speeches by Baldur von Schirach and propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels during the Mozart celebrations bear witness to their disdain for foreigners. The supposed “international” aspect of these events was a mere illusion. Outwardly, they presented a cultured, peaceful image, while Hitler and his generals constantly contemplated war, and thousands of Jews were being incinerated in crematoriums.

Musicology and Nazi Ideals

The SS were tasked not only with protecting the Nazi elite and exterminating those deemed “racially and biologically inferior,” but also with advancing the study of race. Heinrich Himmler funded Joseph Müller-Blattau’s musicological studies on Aryan music, tracing it to folk traditions, and Karl Gustav Fellerer’s efforts to demonstrate the Germanic roots of Gregorian chant with substantial financial backing.

The Lasting Legacy of Nazi Musicology

An authoritative legacy from these “research” efforts was Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart, conceived during the Nazi era. It remained recommended reading during our university days. Friedrich Blume, then editor-in-chief, continued his role unchallenged until 1968, writing further “essential” contributions to modern musicology on Mozart and the “Viennese classicism.”

You May Also Like

#4 The Golden Spur

While often portrayed as a prestigious award, the Golden Spur (Speron d’Oro) granted to Mozart in 1770 was far from a reflection of his musical genius. In this article, we delve into the true story behind this now-forgotten honour, its loss of value, and the role of Leopold Mozart’s ambitions in securing it.

Mozart Unmasked: The Untold Story of His Italian Years

Explore the lesser-known side of Wolfgang Amadé Mozart’s early years in Italy. ‘Mozart in Italy’ unveils the complexities, controversies, and hidden truths behind his formative experiences, guided by meticulous research and rare historical documents. Delve into a story that challenges the traditional narrative and offers a fresh perspective on one of history’s most enigmatic composers.

Another Example of Borrowed Genius

The myth of Mozart’s genius continues to collapse under the weight of his reliance on others’ ideas, with Leopold orchestrating his son’s supposed early brilliance.

A Genius or a Patchwork?

The genius of Mozart had yet to bloom, despite the anecdotes passed down to us. These concertos were not the work of a prodigy, but a collaborative effort between father and son, built on the music of others.

Myth, Reality, and the Hand of Martini

Mozart handed over Martini’s Antiphon, not his own, avoiding what could have been an embarrassing failure. The young prodigy had a lot to learn, and much of what followed was myth-making at its finest.

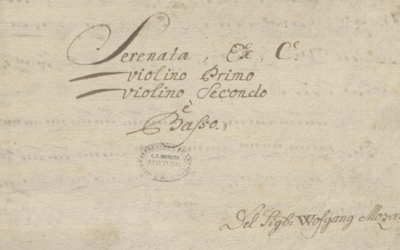

Mozart’s Serenade? A New Discovery? Really?

In Leipzig, what was thought to be a new autograph of Mozart turned out to be a questionable copy. Why are such rushed attributions so common for Mozart, and why is it so hard to correct them when proven false?