Mozart's Letters:

A Legacy of Disappearances, Edits, and Forgeries

Unveiling the Irregularities and Manipulations in Mozart’s Correspondence.

The recently translated letters of Mozart reveal a puzzling pattern of missing originals, dubious authorship, and outright forgeries, casting doubt on the integrity of key documents. This tangled web—particularly within Mozart’s final years—demands a critical look to understand not only the man but also the influence of those who controlled his legacy.

Mozart: The Fall of the Gods

This book compiles the results of our studies on 18th-century music and Mozart, who has been revered for over two centuries as a deity. We dismantle the baseless cult of Mozart and strip away the clichés that falsely present him as a natural genius, revealing the contradictions in conventional biographies. In this work, divided into two parts, we identify and critically analyze several contradictory points in the vast Mozart bibliography. Each of the nearly 2,000 citations is meticulously sourced, allowing readers to verify the findings. This critical biography of Mozart emerges from these premises, addressing the numerous doubts raised by researchers.

"Mozart’s legacy, as seen through these letters, is less a window to the man himself and more a tapestry woven by those around him, where motives, omissions, and secrets were the fabric of his story."

Mozart: The Fall of the Gods

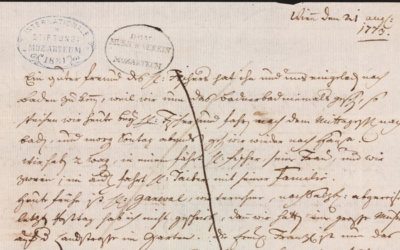

Mozart’s surviving letters, or what remains of them, are filled with glaring inconsistencies. Examining these letters reveals a peculiar narrative: missing originals, questionable entries, and edits that cast doubt on their authenticity and purpose. For example, in 1788, we find only five letters from Mozart, one of which survives only as a copy, while the others simply request funds. In 1791, this increases to 27 letters, yet 13 are not autograph, and 11 bear the “modifications” of his widow Constanze or her second husband, Nissen. The pattern in previous years shows a similarly scattered story.

Leopold’s Letters and a Sparse Record from Wolfgang

The body of correspondence between Mozart and his father, Leopold, could more accurately be called Leopold’s Letters. Up until 1777, roughly 350 letters are from Leopold, compared to only about 25 from Wolfgang. Between 1778 and 1779, Leopold’s 45 letters still exceed Wolfgang’s 30. Only from 1780 to 1783 does Wolfgang’s correspondence increase—about 130 letters, nearly all addressed to his father. After 1784, however, Wolfgang’s letters become sparse: 15 in 1784, then dropping to only two in 1785. While some letters may have been misplaced, others seem to be lost forever—censored, possibly, by later family members like his sister Nannerl and later his wife Constanze, to polish Wolfgang’s image and obscure certain relationships, notably with his former love, Aloysia Weber.

A Reluctant Writer and His Coded Messages

Mozart was hardly a keen letter-writer, tending toward a laziness that made even essential communication difficult. When he did write, he often veiled himself, rarely revealing his true thoughts. In requests for funds, particularly to his friend Johann Michael Puchberg, he seldom conveyed the full story. Sensitive matters, often coded or disguised in playful language, hint at hidden meanings. Some messages were even erased, partially torn, or entirely destroyed. Copying and “enhancing” letters, then discarding originals, was a common tactic used to shape Mozart’s image, whether for financial support, reputation management, or political gain.

The “Letter” to Lorenzo Da Ponte

One particularly disputed letter, supposedly sent to librettist Lorenzo Da Ponte in September 1791, exemplifies these doubts. The sole surviving copy, located in Berlin’s Prussian Library, lacks a signature or named addressee. Additionally, it describes Mozart in a state of extreme depression—at odds with his generally positive disposition despite health challenges. This discrepancy prompted editor Schiedermair to reject the letter as inauthentic.

Titles, Fables, and Imagined Performances

Even where letters are verified as authentic, caution is required. Mozart’s letters occasionally contain exaggerations and untruths: he claimed titles he did not hold, overstated his examination success in Bologna, fabricated concert appearances to justify loan requests, and even invented tales of rivalries. This surviving correspondence—missing, altered, and sometimes fabricated—reveals a portrait of Mozart shaped as much by omission as by his own hand.

You May Also Like

The Violin Concertos: Mozart’s Borrowed Genius

Mozart’s violin concertos are often celebrated as masterpieces, but how much of the music is truly his? This article delves into the complexities behind the compositions and challenges the authenticity of some of his most famous works, revealing a story of influence, imitation, and misattribution.

#2 The Hidden Truth of Mozart’s Education

In this video, we uncover the hidden truth behind Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s early education and challenge the long-held belief in his effortless genius. While history often celebrates Mozart as a child prodigy, effortlessly composing music from a young age, the reality is far more complex.

The London Notebook

The London Notebook exposes the limitations of young Mozart’s compositional skills and questions the myth of his early genius. His simplistic pieces, fraught with errors, reveal a child still grappling with fundamental musical concepts.

The Mozart Question

In this revealing interview, we delve into the lesser-known aspects of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s life, challenging the long-standing myth of his genius. A Swedish journalist explores how Mozart’s legacy has been shaped and manipulated over time, shedding light on the crucial role played by his father, Leopold, in crafting the career of the famed composer.

Georg Nissen and the Missing Notebooks

After Mozart's death, his widow, Constanze, found a steadfast partner in Georg Nikolaus von Nissen, a Danish diplomat who dedicated his life to preserving the composer's legacy. Nissen not only compiled an extensive biography of Mozart but also uncovered and...

Letters Under Surveillance

In a world without privacy, Leopold Mozart’s letters were carefully crafted not just to inform but to manipulate perceptions. His correspondence reveals a calculated effort to elevate his family’s status while avoiding any mention of failure or controversy.