Mozart’s Serenade? A New Discovery? Really?

A Controversial Finding in Leipzig Raises Questions About Mozart’s Authenticity

In Leipzig, what was thought to be a new autograph of Mozart turned out to be a questionable copy. Why are such rushed attributions so common for Mozart, and why is it so hard to correct them when proven false?

Mozart: The Construction of a Genius

This book offers a fresh and critical look at the life of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, challenging the myths that have surrounded him for centuries. We strip away the romanticised image of the “natural genius” and delve into the contradictions within Mozart’s extensive biographies. Backed by nearly 2,000 meticulously sourced citations, this work invites readers to explore a deeper, more complex understanding of Mozart. Perfect for those who wish to question the traditional narrative, this biography is a must-read for serious music lovers and historians.

"The trouble with fiction is that it makes too much sense, whereas reality never makes sense."

Aldous Huxley

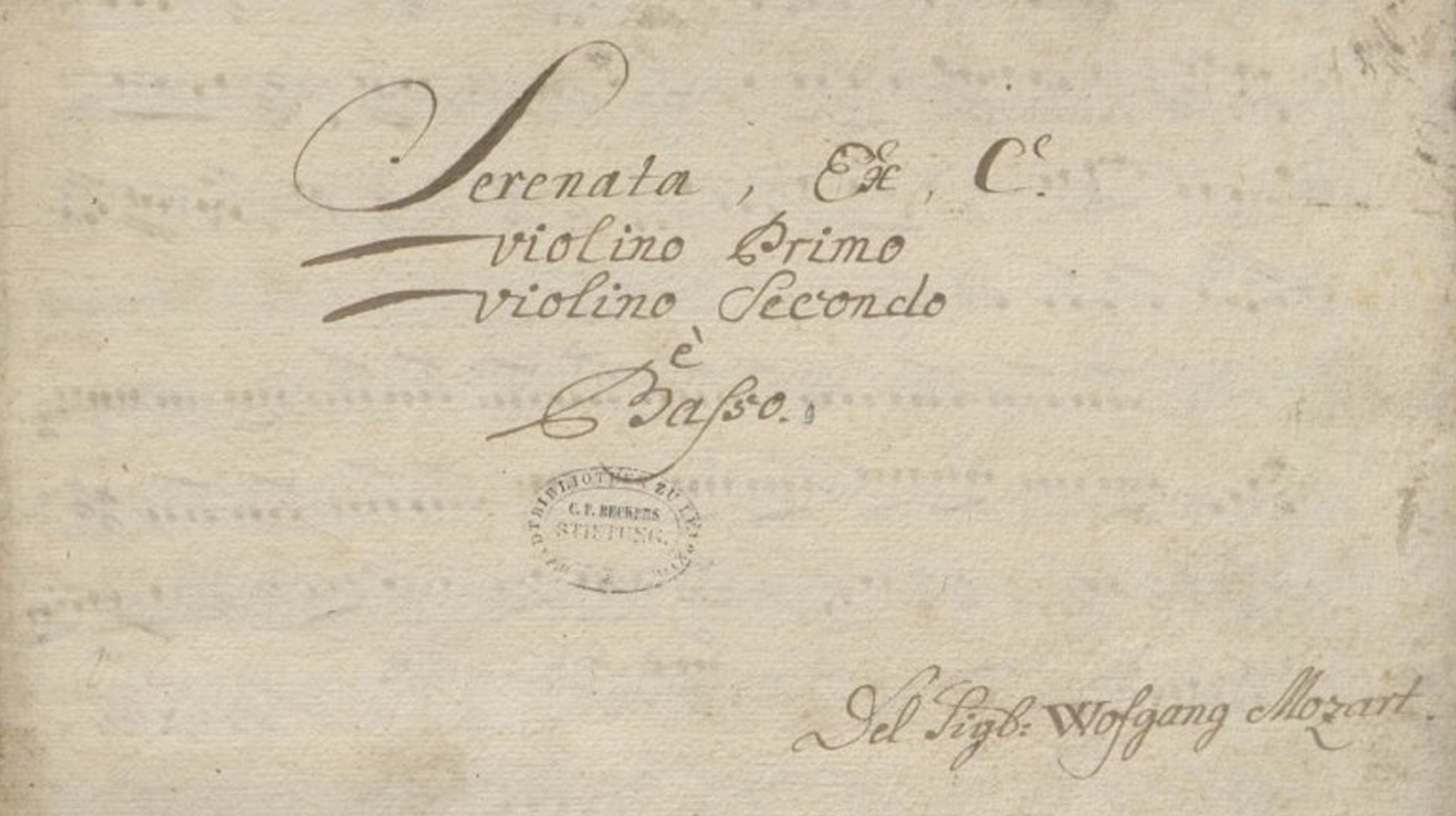

Did Leipzig really uncover a new autograph of Mozart? Not quite. What they found was a copy, and even its dating is questionable. The discussions I’ve come across seem more like speculation, but repeating them doesn’t make them true.

At first glance, the title page might make you think it’s by Mozart, but the piece was actually written by an anonymous copyist about twenty years later—assuming that theory is even accurate. Looking at the title page, the supposed author is a certain “Wofgang” (without the L!).

How can we trust an attribution when the name itself is misspelled? For all we know, the music could have been written by his sister, his aunt, or perhaps even a close friend of Leopold. Essentially, anyone.

Without an autograph, a date, a place, or even the correct name, it was almost predictable that this would be quickly absorbed into the Köchel catalogue of Mozart’s works as another “authentic” piece. It’s fascinating to see how eagerly such attributions are made, especially for a figure as iconic as Mozart.

There’s never this kind of urgency when a work, once attributed to Mozart, turns out to have been written by someone else. In those cases, the opposite happens. Once a piece enters the catalogue, it rarely gets removed, even when the evidence clearly shows it’s a forgery.

You May Also Like

Unveiling the Truth Behind the Drawing

H. S. Brockmeyer’s latest research unravels the mystery behind a July 5, 1791, letter from Mozart to his wife. This remarkable investigation uncovers the original, unembellished drawing Mozart included—vastly different from the altered version widely reproduced in collections today. The discovery raises significant questions about historical accuracy and the intentional shaping of Mozart’s legacy.

The Deceptive Nature of Mozart’s Catalogue

The Thematic Catalogue traditionally credited to Mozart is fraught with inaccuracies, suggesting that many of his famous works might not be his at all. This prompts a necessary reevaluation of Mozart’s legacy and the authenticity of his compositions.

The Mozart Myth Unveiled: A Deeper Look

Mozart’s legacy is far from the untarnished narrative of genius that history would have us believe. The web of deceit woven around his name by those closest to him, including his own widow, reveals a much darker story.

The Other Side of Mozart’s Legacy

Explore the untold story of Mozart, where myth and reality collide. Our critical examination of his life and works reveals a legacy shaped by profit, myth-making, and misattribution. Join us in uncovering the truth behind the man and his music.

The Deception Surrounding Mozart’s Legacy

Anton Eberl’s confrontation with Constanze in 1798 exposed a web of deceit surrounding Mozart’s legacy, revealing that several of his compositions were falsely attributed to the late composer. This chapter uncovers the ethical dilemmas and controversies that have marred the posthumous reputation of one of history’s most celebrated musicians.

Leopold’s Invisible Hand

Behind the glittering performances of young Wolfgang and Nannerl Mozart lay the meticulous guidance of their father, Leopold. Often considered a mere teacher, Leopold’s role in composing and shaping their early musical successes has been largely overlooked. Was the child prodigy truly a genius, or was it Leopold who orchestrated his son’s rise to fame?