Mozart’s Training

The Myth of Genius Shattered

The myth of Mozart’s genius is nothing more than a carefully crafted illusion, propped up by misplaced attributions and romanticised biographies. Behind his so-called brilliance lies the reality of his father’s dominating influence and a lack of formal education.

Mozart: The Fall of the Gods

This book offers a fresh and critical look at the life of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, challenging the myths that have surrounded him for centuries. We strip away the romanticised image of the “natural genius” and delve into the contradictions within Mozart’s extensive biographies. Backed by nearly 2,000 meticulously sourced citations, this work invites readers to explore a deeper, more complex understanding of Mozart. Perfect for those who wish to question the traditional narrative, this biography is a must-read for serious music lovers and historians.

"Mozart’s so-called maturation as a composer was more a product of Leopold’s craft than any external influence."

Mozart: The Fall of the Gods

When it comes to Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, the myth of innate genius has been perpetuated for centuries. But if we strip away the romanticism and look at the facts, a different picture begins to emerge. Far from being a natural-born prodigy, Mozart’s musical abilities were meticulously shaped under the strict and controlling hand of his father, Leopold, and not by some divine inspiration or natural talent.

Mozart’s education was far from conventional. Unlike his father, who received a formal education at the hands of Jesuits, Amadé never attended school. He didn’t have systematic lessons in harmony, counterpoint, or fugue, nor did he benefit from the intellectual and musical training that other musicians of his time received in colleges or religious institutions. His schooling was entirely confined to his father’s relentless tutelage. Yet, for years, biographers have attempted to place Wolfgang under the tutelage of prestigious teachers like Padre Giovanni Battista Martini, despite the glaring lack of evidence.

Martini was a celebrated teacher, whose influence has been exaggerated in Mozart’s case. Theories linking Martini’s teaching to Mozart’s compositions have persisted for years. Musicologists have even gone so far as to analyse Wolfgang’s works before and after his visit to Bologna in 1770 to ‘prove’ the supposed influence of the famed didact. Yet, closer examination reveals these claims to be weak at best. It wasn’t Martini’s guidance that shaped Mozart’s sacred music, but rather the hand of his father.

Mozart’s masses, such as the K.115 and K.116, once hailed as evidence of his development under Martini, have since been attributed to Leopold, not Wolfgang. The more closely we examine the so-called “masterpieces” of Mozart, the more the cracks begin to show. The most embarrassing realisation, however, is that for all of Wolfgang’s supposed “originality,” his most lauded works in sacred music were little more than compositions reworked from his father’s drafts.

In fact, in 1953, Karl Pfannhauser discovered that the Kyrie K.221, Lacrimosa K.Anh.21, and another untitled fragment came from Johann Ernst Eberlin’s Requiem in C Major, a piece once very popular in Austria and certainly admired by the Mozarts. For many years, it was believed that Wolfgang had copied Eberlin’s Lacrimosa, omitting the nine-bar orchestral introduction. However, in 1961, Wolfgang Plath confirmed that all three pieces had actually been copied by Leopold, not Wolfgang. The 1964 Köchel catalogue still included these works under Mozart’s name, but classified them as music that Wolfgang had copied from other composers. Further evidence found after World War II confirmed beyond doubt that the Kyrie K.221 was indeed copied by Leopold.

In reality, the notion that Mozart’s church music owed anything significant to Martini is a fabrication. Wolfgang’s so-called maturation as a composer was more a product of Leopold’s craft than any external influence. This becomes particularly evident in the way Mozart mirrored the style of his father’s compositions and even used entire sections of his father’s work in his own pieces, like the K.115. The narrative that Mozart became “autonomous” through Martini’s teaching is, in fact, a convenient fantasy.

You May Also Like

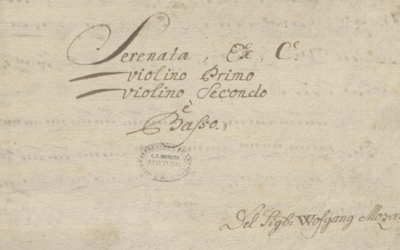

Mozart’s Serenade? A New Discovery? Really?

In Leipzig, what was thought to be a new autograph of Mozart turned out to be a questionable copy. Why are such rushed attributions so common for Mozart, and why is it so hard to correct them when proven false?

Mozart’s K 71: A Fragment Shrouded in Doubt and Uncertainty

Mozart’s K 71, an incomplete aria, is yet another example of musical ambiguity. The fragment’s authorship, dating, and even its very existence as a genuine Mozart work remain open to question. With no definitive evidence, how can this fragment be so confidently attributed to him?

Unpacking Mozart’s Early Education

The story of Ligniville illustrates the pitfalls of romanticizing Mozart’s early life and education, reminding us that the narrative of genius is often a construct that obscures the laborious aspects of musical development.

The False Sonnet of Corilla Olimpica

Leopold Mozart’s relentless pursuit of fame for his son Wolfgang led to questionable tactics, including fabricating a sonnet by the renowned poetess Corilla Olimpica. This desperate attempt to elevate Wolfgang’s reputation casts a shadow over the Mozart legacy.

Mozart’s K 73A: A Mystery Wrapped in Ambiguity

K.143 is a prime example of how Mozart scholarship has turned uncertainty into myth. With no definitive evidence of authorship, date, or purpose, this uninspired recitative and aria in G major likely originated elsewhere. Is it time to admit this is not Mozart’s work at all?

A Farce of Honour in Mozart’s Time

By the time Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart received the Speron d’Oro, the once esteemed honour had become a laughable trinket, awarded through networking and influence rather than merit. Far from reflecting his musical genius, the title, shared with figures like Casanova, symbolised ridicule rather than respect.