The Bologna Exam

Myth, Reality, and the Hand of Martini

Mozart handed over Martini’s Antiphon, not his own, avoiding what could have been an embarrassing failure. The young prodigy had a lot to learn, and much of what followed was myth-making at its finest.

Mozart: The Fall of the Gods

This book compiles the results of our studies on 18th-century music and Mozart, who has been revered for over two centuries as a deity. We dismantle the baseless cult of Mozart and strip away the clichés that falsely present him as a natural genius, revealing the contradictions in conventional biographies. In this work, divided into two parts, we identify and critically analyze several contradictory points in the vast Mozart bibliography. Each of the nearly 2,000 citations is meticulously sourced, allowing readers to verify the findings. This critical biography of Mozart emerges from these premises, addressing the numerous doubts raised by researchers.

"Had Mozart handed in his original composition, the examiners would have failed him. It was Martini’s intervention that secured his place among the Filarmonici."

Mozart: The Fall of the Gods

On 9 October 1770, after a pleasant stay outside the city at Count Pallavicini’s villa, young Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart faced the formidable test to join Bologna’s Accademia Filarmonica. Much like the Marquis de Ligniville before him, Amadé was required to prove his mastery of counterpoint. The task? To compose a strict contrapuntal Antiphon for four voices a cappella, based on a Cantus Firmus. After completing the exam, the following day, Mozart was diplomatically welcomed into the Accademia, but was his composition truly the triumph claimed by his father Leopold and biographer Georg Nissen?

Nissen, keen to portray the boy genius, described the 14-year-old as already proficient in manipulating vocal lines and textures. He claimed that Mozart displayed remarkable contrapuntal skills, deftly juggling rhythmic combinations across the soprano, alto, and tenor parts. His account, however, was largely based on Leopold’s letter, written on 20 October 1770, which was the first source to mention the exam. Nissen and later biographers filled in the gaps with romanticised tales, painting an image of Mozart as a child prodigy beyond reproach.

Early biographers, like Friedrich von Schlichtegroll, Franz Niemetschek, and Stendhal, offered little detail, merely repeating the same sparse information. Over time, more poetic inventions crept in. The 1836 Dizionario Universale della Lingua Italiana, for example, added a whimsical touch: “Mozart, brilliant in his youthful talent, was locked in a room with the theme for a four-part fugue. In just half an hour, he emerged triumphant.” A tale that echoed in many countries, romanticising Mozart’s supposed miraculous achievement, as it fuelled the myth-making that ensued globally.

However, there is a discrepancy between Leopold’s claim that the exam took only half an hour and Mozart’s own account, which says it took him one hour. Even more confusing, other candidates reportedly took three hours according to Leopold, but Mozart stretched that to four or five. It seems Leopold was keen to make his son’s performance appear even more impressive by conveniently halving the time.

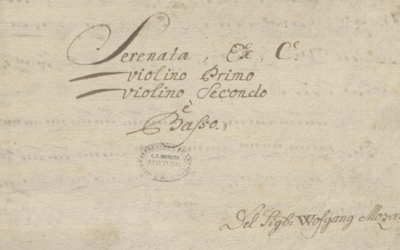

Two years later, in 1858, music historian and composer Gaetano Gaspari published his Sketch of Musical History, which shed new light on the episode. Gaspari discovered that two versions of the Antiphon existed in Bologna’s archives, one by Mozart and the other by his examiner, Padre Giovanni Battista Martini. According to the examination records, the Martini version was the one presented to the filarmonici for approval, not Mozart’s.

Gaspari noted that upon emerging from the exam room, Mozart had handed over Martini’s Antiphon rather than his own. To avoid public embarrassment, Gaspari chose to remain silent for a time, only mentioning the “not entirely innocent fraud” later in a private archive note. He observed that the two versions of the Antiphon showed clear differences.

In 1858, it was no easy task to challenge the reigning narratives about Mozart, especially under the Austrian-dominated censorship in Milan. Gaspari’s subtle revelation went unnoticed by many, as the cultural machinery continued to celebrate Mozart’s supposedly miraculous feats, suppressing any truth that could tarnish the legend.

The Antiphon attributed to Mozart, published by Ricordi, was in fact the version rewritten by Martini, and even the attestation by Martini himself differed slightly from the original manuscript. In reality, Mozart’s attempt did not conform to the strict rules of the genre. The young prodigy, still inexperienced in the ancient style of counterpoint, made several notable errors, particularly in soprano measures three and four, where he incorrectly used direct motion to perfect fifths—something explicitly forbidden by the rules of counterpoint.

Leopold further perpetuated the myth by claiming that Mozart had passed the exam with unanimous approval, receiving all “white balls” (favourable votes). In reality, Mozart passed by the skin of his teeth. Had he submitted the original version of his Antiphon, as he had written it, he would have failed. The examiners recognised his skills as a performer, but not as a composer. Padre Martini’s attestation clearly acknowledged Mozart’s ability as a player, not a composer—another detail conveniently omitted by Leopold in his glorifying narrative.

The myth of Mozart’s infallibility was further entrenched when his revised Antiphon was included in the Köchel catalogue as K.86, perpetuating the misunderstanding for generations to come. However, the truth, uncovered by scholars like Gaspari, shows that Martini’s guidance was crucial in helping Mozart pass the exam. Once again, the legend of Mozart was far removed from the reality of his youthful struggles.

You May Also Like

#3 Leopold Mozart’s Literary Theft

Hidden within the Mozarteum’s archives lies a poem that has long been hailed as a tribute to the young Mozart children. But behind this innocent façade is a story of deception, literary theft, and one father’s ambition to rewrite history.

#4 The Golden Spur

While often portrayed as a prestigious award, the Golden Spur (Speron d’Oro) granted to Mozart in 1770 was far from a reflection of his musical genius. In this article, we delve into the true story behind this now-forgotten honour, its loss of value, and the role of Leopold Mozart’s ambitions in securing it.

Mozart Unmasked: The Untold Story of His Italian Years

Explore the lesser-known side of Wolfgang Amadé Mozart’s early years in Italy. ‘Mozart in Italy’ unveils the complexities, controversies, and hidden truths behind his formative experiences, guided by meticulous research and rare historical documents. Delve into a story that challenges the traditional narrative and offers a fresh perspective on one of history’s most enigmatic composers.

Another Example of Borrowed Genius

The myth of Mozart’s genius continues to collapse under the weight of his reliance on others’ ideas, with Leopold orchestrating his son’s supposed early brilliance.

A Genius or a Patchwork?

The genius of Mozart had yet to bloom, despite the anecdotes passed down to us. These concertos were not the work of a prodigy, but a collaborative effort between father and son, built on the music of others.

Mozart’s Serenade? A New Discovery? Really?

In Leipzig, what was thought to be a new autograph of Mozart turned out to be a questionable copy. Why are such rushed attributions so common for Mozart, and why is it so hard to correct them when proven false?