The Truth Behind Mozart’s Canons

Simplicity, Errors, and the Myth of Perfection

Mozart is often praised as a master of form and complexity, but his canonic output tells a different story. Of the few canons he composed, most are surprisingly simple, often for equal voices and in unison.

However, two canons, K.553 and K.554, stand out not for their brilliance, but for their errors in counterpoint. Additionally, the myth surrounding the canon “V’amo di cuore teneramente” K.348 (K.6 382g) is finally debunked—Mozart never completed it.

The truth about these works paints a less flattering picture of the composer during this period.

Mozart: The Fall of the Gods

This book compiles the results of our studies on 18th-century music and Mozart, who has been revered for over two centuries as a deity. We dismantle the baseless cult of Mozart and strip away the clichés that falsely present him as a natural genius, revealing the contradictions in conventional biographies. In this work, divided into two parts, we identify and critically analyze several contradictory points in the vast Mozart bibliography. Each of the nearly 2,000 citations is meticulously sourced, allowing readers to verify the findings. This critical biography of Mozart emerges from these premises, addressing the numerous doubts raised by researchers.

"The errors in Mozart’s canons, from contrary octaves to parallel fifths, suggest a composer far from the technical perfection often attributed to him."

Mozart: The Fall of the Gods

Mozart is revered as a genius in all aspects of musical composition, but the reality of his canonic output may surprise you. Among the few canons he composed, most are simple, written in unison for equal voices, with little to no complexity. These are far from the intricate counterpoint often associated with his larger works.

Take, for instance, Canone K.553 and K.554, both of which belong to the sacred music genre. K.553 draws on a pre-existing Alleluia melody, while K.554 uses only two words from the Ave Maria. A popular tale claims Mozart composed the latter on the visitor’s register at a Bavarian convent—a charming story that turns out to be nothing more than an invention of the inscription added in 1813.

In reality, the Canone dell’Ave Maria was composed in 1788, during Mozart’s 32nd year. Yet, when compared to his earlier work, it shows signs of regression. The melody disobeys classical counterpoint rules: the vocal line jumps erratically from low to high registers, introduces dissonances, and features awkward harmonic transitions. The entire piece is anchored in F major, with only a single passing modulation. Mozart, by this stage, should have known better, especially given the polished works he produced in that same year.

The errors are glaring. Contrary octaves, parallel fifths, diminished fifths—it reads like a checklist of mistakes no 18th-century composer should have made. These failures are incompatible with the rest of Mozart’s output in 1788, a year marked by his great symphonies, which followed the strict compositional rules of the time.

K.553 fares no better. While the melody flows through stepwise motions and broader notes, the harmonic structure is riddled with unresolved dissonances and awkward chromatic sequences. Simple modulations from C major to A minor offer little in the way of ingenuity, and once again, Mozart fails to meet the basic expectations of counterpoint. The piece is littered with parallel fifths and octaves, with dissonances that clash in a way that suggests not innovation, but error.

One rare exception is V’amo di cuore teneramente K.348, written in G major for 12 voices divided into three four-part choirs. Here, imitation takes center stage, but even this work is not without its issues. Mozart left the piece unfinished, and it was later completed by Maximilian Stadler. Constanze, Mozart’s widow, even confirmed in a letter to Johann Anton André that Stadler was responsible for the missing sections. So, even this more elaborate canon does not fully belong to Mozart.

Ultimately, these works challenge the myth of Mozart’s perfection, revealing that even in his later years, his compositional skills were far from flawless.

You May Also Like

The Enigma of Mozart’s Symphony K.73

The Symphony in C Major K.73 has long puzzled Mozart scholars. Touted as a youthful work of prodigious talent, its origins are murky at best. The title “Symphony,” inscribed on the first page of the autograph, is devoid of the composer’s name, casting immediate doubt on its attribution to Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Was this truly his work, or is the Symphony yet another victim of overzealous attribution?

Mozart’s Thematic Catalogue Exposed as a Forgery

A groundbreaking forensic analysis reveals that Mozart’s thematic catalogue, long thought to be his own work, is a posthumous forgery. This discovery, detailed in Mozart: The Construction of a Genius, turns centuries of Mozart scholarship on its head, demanding a re-examination of his legacy.

Bologna Connections

Quirino Gasparini’s rediscovered Mitridate aria takes centre stage in Bern and Basel, shedding light on Mozart’s reliance on this forgotten composer.

International Traetta Award

We are thrilled to announce that the 14th International Traetta Award has been bestowed upon Anna Trombetta and Luca Bianchini. This prestigious recognition honours their outstanding dedication to musicological research on primary sources of the European musical repertoire, offering significant contributions to reshaping the historiography of 18th-century music.

A Legacy Rewritten by the Shadows of History

Mozart’s image, often regarded as a universal symbol of musical genius, was heavily manipulated by the Nazi regime, a fact largely ignored in post-war efforts to “denazify” German culture. From propaganda-driven films to anti-Semitic narratives, Mozart’s legacy is far more complex and troubling than we are often led to believe.

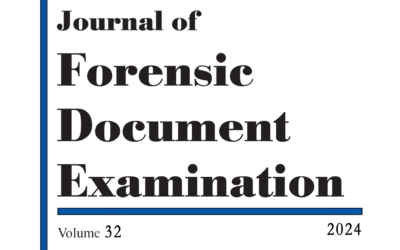

Unveiling the Truth Behind Mozart’s Thematic Catalogue

Anna Trombetta, Professor Martin W. B. Jarvis from Charles Darwin University, and Luca Bianchini, have published a peer-reviewed article titled Unveiling a New Sophisticated Ink Analysis Technique, and Digital Image Processing: A Forensic Examination of Mozart’s Thematic Catalogue. This research, which underwent an extensive double-blind peer review, has appeared in a journal that serves as a global reference point for forensic document examiners and court specialists.