Leopold Mozart

The Ambiguous Legacy of Leopold Mozart: A Man of Cunning and Adaptation

This post explores the multifaceted and often controversial life of Leopold Mozart, providing insight into the complexities and contradictions that defined his career and legacy.

Mozart in Italy: The Untold Story

Was Mozart truly a solitary genius, or was he merely the instrument of his father’s ambition? “Mozart in Italy” challenges the conventional narrative, revealing a complex dynamic between father and son that shaped the course of music history. Prepare to question everything you thought you knew.

“In a letter now astounding for its falsehoods, Leopold lied about his still-living father, claiming the old bookbinder had sent him to Salzburg for studies (avoiding mention of that academic disaster)”

Mozart in Italy

Leopold Mozart, often overshadowed by the brilliance of his son Wolfgang, led a life marked by ambition, cunning, and a series of compromises that both defined and limited his legacy. Despite his lifelong service under five archbishops and seven Kapellmeisters in Salzburg, Leopold never rose above the rank of deputy Kapellmeister. His musical training was largely self-taught, honed through practical experience rather than formal education, which limited his ascent in the highly competitive world of 18th-century music.

Leopold’s career was not without its share of scandals and setbacks. One of the most infamous incidents was his anonymous pamphlet that mocked a cathedral canon—a move that nearly destroyed his reputation. This public humiliation left him deeply scarred and fuelled a newfound cynicism. In a bid to restore his standing, Leopold crafted another anonymous work, this time targeting his fellow musicians in Salzburg. Posing as a newly arrived music lover, he cleverly promoted his own talents while subtly undermining his colleagues. This act of self-promotion, laced with fabrications about his expertise in counterpoint, philosophy, and law, was a testament to his resourcefulness, even if it came at the cost of honesty.

Leopold’s self-aggrandising efforts extended beyond pamphlets. His 1756 publication, “Violinschule,” is often regarded as his most significant contribution to music. Yet, even this work was not entirely original, heavily borrowing from the methods and teachings of other composers like Pietro Antonio Locatelli, Francesco Geminiani, and Giuseppe Tartini. Leopold presented these insights as his own, with little to no acknowledgment of the true sources. This act of appropriation reveals a man who, while not a virtuoso or a celebrated composer, knew how to adapt and repurpose the work of others to fit his ambitions.

Despite these efforts, Leopold struggled with professional frustration. His aspirations for greater recognition were frequently thwarted, and he found himself relegated to the modest court orchestra in Salzburg. To make ends meet, he supplemented his income by giving private lessons, copying scores, and selling compositions—some of which were likely cobbled together from the works of others and passed off as his own. His correspondence with his publisher, Lotter, paints a picture of a man constantly scrambling to maintain his reputation, often at the expense of integrity.

Leopold’s relationship with his family was equally complex. His manipulation of his mother for financial gain, his secret marriage to Anna Maria Pertl, and the subsequent estrangement from his family in Augsburg reflect a man who was willing to deceive those closest to him to achieve his goals. This rift was painfully evident when, years later, his grandchildren, Wolfgang and Nannerl, performed in Augsburg without their grandmother present in the audience.

In the end, Leopold Mozart’s life was a testament to survival in a world where his talents were often overshadowed by those of his more gifted contemporaries and his own son. While his “Violinschule” remains a notable contribution to music pedagogy, it is clear that Leopold’s legacy is as much about his ability to navigate the challenges of his time as it is about his musical achievements. His story is one of ambition, adaptation, and the lengths to which one man would go to secure his place in history, even if that place was built on borrowed foundations.

You May Also Like

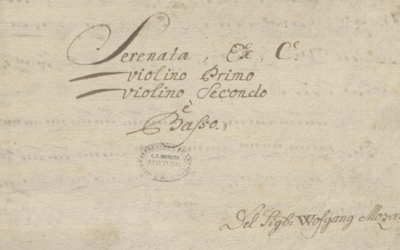

Mozart’s Serenade? A New Discovery? Really?

In Leipzig, what was thought to be a new autograph of Mozart turned out to be a questionable copy. Why are such rushed attributions so common for Mozart, and why is it so hard to correct them when proven false?

Mozart’s K 71: A Fragment Shrouded in Doubt and Uncertainty

Mozart’s K 71, an incomplete aria, is yet another example of musical ambiguity. The fragment’s authorship, dating, and even its very existence as a genuine Mozart work remain open to question. With no definitive evidence, how can this fragment be so confidently attributed to him?

Unpacking Mozart’s Early Education

The story of Ligniville illustrates the pitfalls of romanticizing Mozart’s early life and education, reminding us that the narrative of genius is often a construct that obscures the laborious aspects of musical development.

The False Sonnet of Corilla Olimpica

Leopold Mozart’s relentless pursuit of fame for his son Wolfgang led to questionable tactics, including fabricating a sonnet by the renowned poetess Corilla Olimpica. This desperate attempt to elevate Wolfgang’s reputation casts a shadow over the Mozart legacy.

Mozart’s K 73A: A Mystery Wrapped in Ambiguity

K.143 is a prime example of how Mozart scholarship has turned uncertainty into myth. With no definitive evidence of authorship, date, or purpose, this uninspired recitative and aria in G major likely originated elsewhere. Is it time to admit this is not Mozart’s work at all?

A Farce of Honour in Mozart’s Time

By the time Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart received the Speron d’Oro, the once esteemed honour had become a laughable trinket, awarded through networking and influence rather than merit. Far from reflecting his musical genius, the title, shared with figures like Casanova, symbolised ridicule rather than respect.