Truth or Deception?

The Curious Case of Mozart’s "Lullaby"

Examining the murky history of “Schlafe mein Prinzchen, schlaf ein” and its questionable authorship

In the sprawling world of Mozartian myths, few tales have endured as long or as stubbornly as the origins of the lullaby Schlafe mein Prinzchen, schlaf ein (“Sleep, My Little Prince, Go to Sleep”).

For nearly two centuries, this piece has been attributed to Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, despite enduring questions over its authenticity.

First published by Nissen, Constanze Mozart’s second husband, it was only in 1826 that he informed publisher André of the piece’s dubious provenance. While “experts,” Nissen claimed, deemed it worthy of Mozart, Mozart’s sister, Nannerl, held no memory of her brother writing such a tune.

Intriguingly, Constanze, usually vocal in promoting her husband’s legacy, made no public comment, though her personal diary reveals a hint. In a September 17, 1798 entry, she wrote of sending “another piece of Mozart’s in place of the lullaby” to Dr. Feuerstein. Did she suspect, even then, that Mozart may not have authored this work?

Mozart: The Fall of the Gods

This book compiles the results of our studies on 18th-century music and Mozart, who has been revered for over two centuries as a deity. We dismantle the baseless cult of Mozart and strip away the clichés that falsely present him as a natural genius, revealing the contradictions in conventional biographies. In this work, divided into two parts, we identify and critically analyze several contradictory points in the vast Mozart bibliography. Each of the nearly 2,000 citations is meticulously sourced, allowing readers to verify the findings. This critical biography of Mozart emerges from these premises, addressing the numerous doubts raised by researchers.

"Truth in music, as in history, requires more than wishful attribution."

Mozart: The Fall of the Gods

Constanze’s Unreliable Testament

Constanze Mozart remains a controversial source on matters of Mozart’s oeuvre. Could her diary entry imply her own doubts? Over time, the lullaby’s shaky origins gained traction, with figures like Johann Evangelist Engl, a prominent advocate of Mozart’s legacy, affirming the lullaby’s authenticity in the 1892 Annual Report of the Mozarteum. His stance solidified the piece in the Köchel catalogue as K.350. But musicologist Max Friedländer refuted this claim, proving that this celebrated lullaby was, in fact, the work of Bernhard Flies, a minor composer who published it in 1795. Later research revealed that even Flies had borrowed it from an earlier melody by Johann Friedrich Anton Fleischmann. Over time, Fleischmann’s lullaby became mistakenly attributed to Flies, then to Mozart—a confusion that would last over fifty years and persist, falsely, to this day.

An Ideological Battle for “Mozart’s” Lullaby

In 1944, as authenticity disputes resurfaced, German musicologist Herbert Gerigk, known for his involvement with Nazi-aligned musical publications, took a vehement stance. For Gerigk, Friedländer and Einstein’s work discrediting the lullaby’s Mozartian origins was not just a scholarly objection—it was an affront to Aryan cultural purity. Rather than acknowledging scholarly evidence, he painted Flies, Friedländer, and Einstein as scheming Jewish interlopers. “The German people desire this piece for Mozart,” he argued, sidestepping questions of authenticity in favor of ideology. The result was a chilling example of musical propaganda in service of the regime.

The Apocryphal Piece That Refuses to Die

Today, this questionable lullaby persists in Mozart’s name, nestled innocuously among beginner’s scores. My First Book of Mozart, arranged by David Dutkanicz, includes it as a legitimate Mozartian work, and the Mozart-Schaum Edition, aimed at young pianists, introduces it as “authentic.” Both editions acknowledge its contentious history only in modest footnotes, offering a single line to hint at the debate: “Most people believe this to be Mozart’s work, others say it is spurious.” But, one might ask, does this vague disclaimer suffice to remedy two centuries of mistaken identity?

You May Also Like

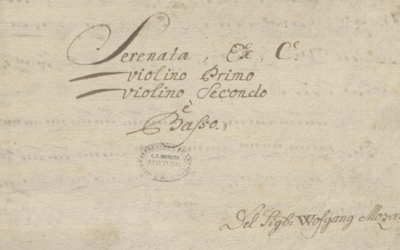

Mozart’s Serenade? A New Discovery? Really?

In Leipzig, what was thought to be a new autograph of Mozart turned out to be a questionable copy. Why are such rushed attributions so common for Mozart, and why is it so hard to correct them when proven false?

Mozart’s K 71: A Fragment Shrouded in Doubt and Uncertainty

Mozart’s K 71, an incomplete aria, is yet another example of musical ambiguity. The fragment’s authorship, dating, and even its very existence as a genuine Mozart work remain open to question. With no definitive evidence, how can this fragment be so confidently attributed to him?

Unpacking Mozart’s Early Education

The story of Ligniville illustrates the pitfalls of romanticizing Mozart’s early life and education, reminding us that the narrative of genius is often a construct that obscures the laborious aspects of musical development.

The False Sonnet of Corilla Olimpica

Leopold Mozart’s relentless pursuit of fame for his son Wolfgang led to questionable tactics, including fabricating a sonnet by the renowned poetess Corilla Olimpica. This desperate attempt to elevate Wolfgang’s reputation casts a shadow over the Mozart legacy.

Mozart’s K 73A: A Mystery Wrapped in Ambiguity

K.143 is a prime example of how Mozart scholarship has turned uncertainty into myth. With no definitive evidence of authorship, date, or purpose, this uninspired recitative and aria in G major likely originated elsewhere. Is it time to admit this is not Mozart’s work at all?

A Farce of Honour in Mozart’s Time

By the time Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart received the Speron d’Oro, the once esteemed honour had become a laughable trinket, awarded through networking and influence rather than merit. Far from reflecting his musical genius, the title, shared with figures like Casanova, symbolised ridicule rather than respect.