Wolfgang Amadé Mozart

The Deceptive Nature of Mozart’s Catalogue

The Thematic Catalogue traditionally credited to Mozart is fraught with inaccuracies, suggesting that many of his famous works might not be his at all. This prompts a necessary reevaluation of Mozart’s legacy and the authenticity of his compositions.

“If Mozart had truly authored the Catalogue, he would not have mistakenly attributed the Arietta K. 541 to a bass when it was clearly intended for a tenor-baritone, casting further doubt on the document’s authenticity.”

Mozart: The Construction of a Genius

The Questionable Authenticity of K. 456

The legitimacy of Mozart’s Thematic Catalogue has long been debated, particularly regarding the inclusion of the Concerto K. 456 for Harpsichord and Orchestra, supposedly composed for the blind harpsichordist Teresa Paradis. The Catalogue indicates that the piece was completed on 30 September, just two days before Paradis’s final performance in Paris on 2 October. This timeline raises serious doubts. It seems highly unlikely that Mozart could have composed the Concerto, prepared all the necessary parts, and sent them to Paris in such a short span. The inclusion of this Concerto in the Catalogue without addressing these logistical challenges suggests a likely error or falsification in the dating.

Inconsistencies Surrounding K. 541

Further inconsistencies arise with the Arietta for Bass, K. 541, titled ‘Un bacio di mano’. The Catalogue lists this work as composed in May, yet it was later included in a Viennese revival of Pasquale Anfossi’s opera that same year. The Catalogue incorrectly attributes the performance to the famous bass Albertarelli, while in reality, it was sung by the tenor-baritone Del Sole. Such a mistake would be improbable if Mozart himself had recorded the information, casting further doubt on the Catalogue’s authenticity.

The Mystery of the Jupiter Symphony (K. 551)

The doubts surrounding Mozart’s Catalogue also extend to the famous Jupiter Symphony (K. 551). Some scholars point to similarities between this Symphony and the Arietta K. 541 to support Mozart’s authorship. However, if K. 541 was wrongly attributed to Mozart, the legitimacy of the Jupiter Symphony’s attribution is also questionable. Moreover, the original manuscript of the Symphony lacks Mozart’s signature or date, leading to speculation that the Catalogue was compiled posthumously to attribute this and other works to Mozart without solid evidence.

Discrepancies in Other Works

Questions also surround the authenticity of the Trio for Harpsichord, Violin, and Cello, K. 564, and the Masonic music, K. 477. Both works are listed in Mozart’s Catalogue, but with suspicious details that suggest someone else may have composed or copied them. The strikingly similar handwriting between the Catalogue and the manuscripts suggests potential forgery. Albert Osborn, a scholar on falsifications, argued that anyone who reproduces handwriting exactly is likely a forger, as it is impossible for a person to replicate the same phrase, musical passage, or signature identically multiple times.

Conclusion: A Catalogue of Errors

Often regarded as a definitive record of Mozart’s works, the Thematic Catalogue is fraught with inaccuracies, questionable attributions, and possible forgeries. These issues indicate that much of what has been traditionally accepted about Mozart’s later works, including some of his most celebrated compositions, may not be as it seems.

The discrepancies found in the Catalogue suggest it was likely created after Mozart’s death, potentially by those with an interest in enhancing his legacy. Given all these contradictions, the authenticity of many works attributed to Mozart must be reconsidered.

Journal of Forensic Document Examination

Mozart’s Catalogue Exposed

You May Also Like

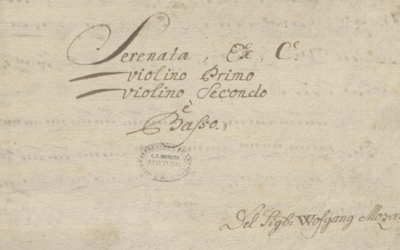

Mozart’s Serenade? A New Discovery? Really?

In Leipzig, what was thought to be a new autograph of Mozart turned out to be a questionable copy. Why are such rushed attributions so common for Mozart, and why is it so hard to correct them when proven false?

Mozart’s K 71: A Fragment Shrouded in Doubt and Uncertainty

Mozart’s K 71, an incomplete aria, is yet another example of musical ambiguity. The fragment’s authorship, dating, and even its very existence as a genuine Mozart work remain open to question. With no definitive evidence, how can this fragment be so confidently attributed to him?

Unpacking Mozart’s Early Education

The story of Ligniville illustrates the pitfalls of romanticizing Mozart’s early life and education, reminding us that the narrative of genius is often a construct that obscures the laborious aspects of musical development.

The False Sonnet of Corilla Olimpica

Leopold Mozart’s relentless pursuit of fame for his son Wolfgang led to questionable tactics, including fabricating a sonnet by the renowned poetess Corilla Olimpica. This desperate attempt to elevate Wolfgang’s reputation casts a shadow over the Mozart legacy.

Mozart’s K 73A: A Mystery Wrapped in Ambiguity

K.143 is a prime example of how Mozart scholarship has turned uncertainty into myth. With no definitive evidence of authorship, date, or purpose, this uninspired recitative and aria in G major likely originated elsewhere. Is it time to admit this is not Mozart’s work at all?

A Farce of Honour in Mozart’s Time

By the time Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart received the Speron d’Oro, the once esteemed honour had become a laughable trinket, awarded through networking and influence rather than merit. Far from reflecting his musical genius, the title, shared with figures like Casanova, symbolised ridicule rather than respect.