The Forgotten Viennese Quartets

Mozart’s Lost Compositions or Mere Exercises?

The six “Viennese” quartets, composed by Mozart under the supervision of his father, remained hidden from public knowledge for over a decade.

There is no certainty they were written in Vienna during the summer of 1773, as claimed by scholars. Curiously, neither Leopold nor Wolfgang mention these works in their letters, and no trace of a patron or public performance exists for these or other quartets written between 1770 and 1773.

The pieces surfaced only in 1785, leading to speculation that Mozart himself had forgotten them or that they were insignificant exercises in his compositional development. Despite later attempts to produce quartets for wealthy patrons,

Mozart’s efforts in this genre during the 1770s and early 1780s show little progress, leaving more questions than answers about their true purpose and value.

Mozart: The Fall of the Gods

This book compiles the results of our studies on 18th-century music and Mozart, who has been revered for over two centuries as a deity. We dismantle the baseless cult of Mozart and strip away the clichés that falsely present him as a natural genius, revealing the contradictions in conventional biographies. In this work, divided into two parts, we identify and critically analyze several contradictory points in the vast Mozart bibliography. Each of the nearly 2,000 citations is meticulously sourced, allowing readers to verify the findings. This critical biography of Mozart emerges from these premises, addressing the numerous doubts raised by researchers.

"Did Mozart forget about these quartets because they were of no real significance, or was their obscurity a sign of deeper issues in his compositional journey?"

Mozart: The Fall of the Gods

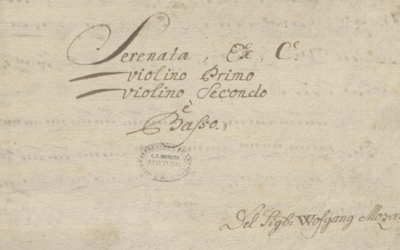

Shortly after his experiences in Milan, Mozart crafted six “Viennese” quartets under the watchful eye of his ever-present father. Yet, these works remained hidden for over a decade. It is far from certain that they were composed in Vienna between July and September of 1773, as suggested by the Neue Mozart-Ausgabe (NMA). Neither Leopold nor Wolfgang’s letters make any mention of these compositions, nor do they reference any potential patron.

We have no records of public performances of these Viennese quartets, nor of those composed in Lodi or Milan. Thirteen quartets written between March 15, 1770, and mid-September 1773, and not a single documented concert, nor a printed edition.

Nothing was known about these pieces until 1785. Mozart didn’t even offer them to his compatriot Jean Georges Sieber, a Parisian publisher, in 1783. It seemed as though he had completely forgotten about them, almost as if he wasn’t their author. These quartets did not represent any notable compositional development for Mozart; they didn’t serve as a stepping stone in mastering the string quartet form. Indeed, only a few years later, Mozart struggled to satisfy an order from an amateur Dutch patron for a set of string quartets and flute pieces.

During the period between his journeys to Mannheim and Paris (1777-78) and his stay in Munich, Mozart composed more quartets—four with flute and one with oboe—but these are marked by little value and a style already out of fashion. Three of the flute quartets (K.285, K.285a, and K. Anh.171) were commissioned by a certain monsieur Dejean in Mannheim, a wealthy Dutch amateur. Mozart reportedly composed these reluctantly (at least, so claim German musicologists eager to excuse the resulting failures), without feeling any particular artistic ambition. Unsurprisingly, Mozart faced difficulties in securing payment from Dejean, likely because only the first quartet in D major met the patron’s expectations in terms of style, content, and length, being structured in three movements (the others are in just two).

You May Also Like

#4 The Golden Spur

While often portrayed as a prestigious award, the Golden Spur (Speron d’Oro) granted to Mozart in 1770 was far from a reflection of his musical genius. In this article, we delve into the true story behind this now-forgotten honour, its loss of value, and the role of Leopold Mozart’s ambitions in securing it.

Mozart Unmasked: The Untold Story of His Italian Years

Explore the lesser-known side of Wolfgang Amadé Mozart’s early years in Italy. ‘Mozart in Italy’ unveils the complexities, controversies, and hidden truths behind his formative experiences, guided by meticulous research and rare historical documents. Delve into a story that challenges the traditional narrative and offers a fresh perspective on one of history’s most enigmatic composers.

Another Example of Borrowed Genius

The myth of Mozart’s genius continues to collapse under the weight of his reliance on others’ ideas, with Leopold orchestrating his son’s supposed early brilliance.

A Genius or a Patchwork?

The genius of Mozart had yet to bloom, despite the anecdotes passed down to us. These concertos were not the work of a prodigy, but a collaborative effort between father and son, built on the music of others.

Myth, Reality, and the Hand of Martini

Mozart handed over Martini’s Antiphon, not his own, avoiding what could have been an embarrassing failure. The young prodigy had a lot to learn, and much of what followed was myth-making at its finest.

Mozart’s Serenade? A New Discovery? Really?

In Leipzig, what was thought to be a new autograph of Mozart turned out to be a questionable copy. Why are such rushed attributions so common for Mozart, and why is it so hard to correct them when proven false?