Unpacking Mozart's K.89

Unpacking Mozart's K.89

This post explores the simplistic nature of Mozart’s Kyrie K.89, revealing the truth behind his early canonic compositions and their implications on his perceived genius.

Mozart: The Fall of the Gods

This book offers a fresh and critical look at the life of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, challenging the myths that have surrounded him for centuries. We strip away the romanticised image of the “natural genius” and delve into the contradictions within Mozart’s extensive biographies. Backed by nearly 2,000 meticulously sourced citations, this work invites readers to explore a deeper, more complex understanding of Mozart. Perfect for those who wish to question the traditional narrative, this biography is a must-read for serious music lovers and historians.

"The incapacity to adhere to compositional rules illustrates the absence of a school and a teacher; mere imitation does not equate to mastery."

Mozart: The Fall of the Gods

When we think of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, the image of a prodigious genius often overshadows the reality of his musical development. One area of his work that deserves scrutiny is his treatment of canons, particularly in his Kyrie K.89. While canons are frequently seen as an entry point into the world of polyphony, Mozart’s versions reveal a stark simplicity that belies the complexities often associated with great composers.

The canon, a straightforward and rigorous compositional technique, is typically the first form grasped by children learning music. Yet, Mozart’s attempts at this form in his K.89 are fundamentally elementary, mainly employing unison voices and imitating the style of his supposed mentor, the Marchese de Ligniville. The notion that these canons serve as evidence of Mozart’s mastery of counterpoint is questionable, as his works primarily reflect a lack of deeper understanding rather than a profound artistry.

Many scholars, including Hermann Abert and Neal Zaslaw, have suggested that Mozart may have benefitted from Ligniville’s teachings during a brief stay in Florence. However, the reality of this mentorship remains vague, with only a few days available for instruction. The assertion that K.89 demonstrates Mozart’s familiarity with counterpoint is undermined by its reliance on copying rather than original composition. The piece consists of merely repeating simple motifs, leading to a product that lacks musical depth and sophistication.

The K.89 is essentially a pastiche, with Mozart replicating two-bar and three-bar phrases rather than crafting a genuinely innovative work. This method of composition results in a repetitive structure that fails to engage the listener on any meaningful level. Critics have noted that the final cadenza is riddled with compositional errors, indicating a lack of guidance and proper schooling in counterpoint.

Furthermore, the idea that K.89 should be held up as a testament to Mozart’s genius is misguided. The work serves as a reminder of the danger in romanticising his early output. While Mozart may have been adept at imitating others, true innovation and mastery require more than mere replication; they necessitate a comprehensive understanding of musical language and form.

In essence, K.89 stands as a historical curiosity rather than a hallmark of genius. It exemplifies the early stages of a composer still grappling with the fundamental principles of music rather than demonstrating an accomplished mastery of the craft.

You May Also Like

The Ambiguous Legacy of Leopold Mozart

This post explores the multifaceted and often controversial life of Leopold Mozart, providing insight into the complexities and contradictions that defined his career and legacy.

The Myth of Mozart

A critical examination of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s life reveals a man shaped more by his father’s ambitions than by innate genius. Stripped of the myths, Mozart’s early years reflect a childhood dominated by relentless touring, inconsistent education, and a legacy built on exaggerated achievements. Discover the real story behind the legend.

The Return of Gatti’s Aria

In the magnificent Max Joseph Hall of the Residenz München, tenor Daniel Behle performed the aria “Puoi vantar le tue ritorte” by Luigi Gatti, taken from his opera Nitteti. This concertante piece, for which we composed the cadenzas, was brought to life by the Salzburger Hofmusik orchestra under the direction of Wolfgang Brunner.

#1 A Man of Cunning

In the end, Leopold Mozart’s life was a testament to survival in a world where his talents were often overshadowed by those of his more gifted contemporaries and his own son. While his “Violinschule” remains a notable contribution to music pedagogy, it is clear that Leopold’s legacy is as much about his ability to navigate the challenges of his time as it is about his musical achievements. His story is one of ambition, adaptation, and the lengths to which one man would go to secure his place in history, even if that place was built on borrowed foundations.

@MozartrazoM

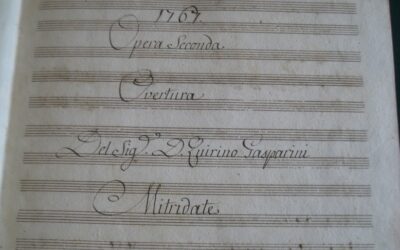

Quirino Gasparini’s Music Performed for the First Time

For the first time in modern history, Quirino Gasparini’s music has been performed. This concert, featuring arias from Mitridate and Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony, was conducted by Maestro Leonardo Muzii, with soprano Anastasiia Petrova.

Teaching Mozart at Bocconi University

We delivered a four-hour lecture on Mozart at Bocconi University, showcasing unpublished music by Gasparini, Gatti, and Tozzi while comparing textual and musical treatment with Mozart’s works. Unseen variants from Le Nozze di Figaro were also revealed.