The London Pieces

Mozart or Make-Believe?

The Neue Mozart-Ausgabe presents Mozart’s London pieces with “ossia” corrections, as if Mozart intended something else altogether. But by “correcting” his harmonic errors, editors obscure the authentic work of a child.

The original simplicity is transformed, commercialized even, to fit expectations of musical genius. As Erik Smith’s orchestral interpretations reveal, this approach can shift a child’s keyboard piece into something unrecognizable, making it not Mozart’s music, but his own.

For those seeking Mozart’s true voice, only the unaltered originals reveal the budding, imperfect composer he truly was.

Mozart: The Fall of the Gods

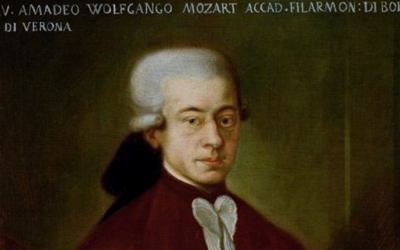

This book compiles the results of our studies on 18th-century music and Mozart, who has been revered for over two centuries as a deity. We dismantle the baseless cult of Mozart and strip away the clichés that falsely present him as a natural genius, revealing the contradictions in conventional biographies. In this work, divided into two parts, we identify and critically analyze several contradictory points in the vast Mozart bibliography. Each of the nearly 2,000 citations is meticulously sourced, allowing readers to verify the findings. This critical biography of Mozart emerges from these premises, addressing the numerous doubts raised by researchers.

"The ‘Viennese Classicism’ was no school but a convenient label—one crafted to advance imperial interests and later twisted to satisfy nationalist agendas."

Mozart: The Fall of the Gods

How many “corrections” does it take before it’s no longer Mozart?

The London pieces, cataloged by Köchel from K.15a to K.15ss, appear in the Neue Mozart-Ausgabe (NMA), the critical edition of Mozart’s works. Where errors appear in Mozart’s original transcriptions, the NMA inserts “ossia” notations, offering “corrected” staves alongside Mozart’s manuscript. As if suggesting Mozart intended “something else,” these ossias mask the reality of what he actually wrote. For instance, in the K.15e, the NMA edits away parallel fifths (G-D, A-E) in measures two and three and revises the final cadence, ridding the piece of octave parallels in the upper parts (A-A, G-G).

While the NMA is diligent in flagging harmonic errors, a problem arises when pianists or record labels, like Philips, perform the ossia instead of Mozart’s original notes. The genuine composition should be accepted as is, with all its charming naïveté; it’s a composition of a young child, after all. Alter it, and it’s no longer music by Wolfgang Mozart. It then shifts from musicological relevance to a simple commercial product.

Above, we see another example of an ossia attached to K.15t, where any harpsichordist who plays this “suggested” version strays far from what young Mozart intended. Such melodic uncertainties are characteristic of an eight-year-old still learning the basics of composition. They shouldn’t be corrected—they represent his knowledge at the time, marking the starting point of his compositional journey. In K.15s, we see, for instance, a descending seventh leap in the bass (B-C), a choice no seasoned composer of the time would have made.

Erik Smith, who worked on the Complete Mozart Edition for Philips, pushes these edits even further. In the CD notes, he calls Mozart’s autographs “filled with smudges and errors” and remarks that, though the pieces sound unremarkable on piano, “the boy obviously heard this music in his head, mostly as orchestral music.” Smith’s claim is puzzling, especially as the pieces fit well on the keyboard, with manageable intervals and straightforward modulations from tonic to dominant and back. These are brief, 16-measure pieces—perfectly pianistic and easy to perform, even by second-year students. Though Smith may try to mask their structural simplicity through editorial changes, these corrections, with revised fifths, octaves, and the final cadence, create a sound that is not Mozart’s.

Smith insists that K.15t, like similar pieces, is more like a sketch, justifying his orchestral reinterpretation based on “intuition over analysis.” He omits less “interesting” sections, reimagining three-quarters of the pieces as “orchestral sounds young Wolfgang might have heard in his head.” This is nothing short of an “impossible endeavor.” Smith’s editorial decisions raise concerns about whether historical scholarship has a place in the paranormal. Claiming to divine the thoughts of a composer dead two centuries is no method for reliable transcription; Smith’s “reinterpretation” becomes, instead, his own original composition, one that accrues royalties under his name. The Philips CD box set, Mozart, rarities & surprises, no doubt “surprised” many listeners to find the music was not Mozart’s but Smith’s. Only in the liner notes is this mentioned, not on the packaging. And what’s more, simple harpsichord pieces hardly qualify as Beethovenian sketches in need of orchestration.

Gustav Mahler (1860–1911) famously orchestrated “Frère Jacques” (also known as “Are You Sleeping”) in his first symphony, making it his own. Likewise, an orchestral K.15e becomes a composition of Smith’s, not Mozart’s. To appreciate Mozart’s original work, we need the harpsichord version, freed from NMA’s corrections and the Romantic assumption that Mozart composed flawlessly.

Ultimately, these London pieces hardly resemble the works of a prodigious miracle: young Mozart succeeds at times, particularly when staying within the bounds of childhood playfulness. But taken as a whole, these works reveal his status as a mere novice or even, on occasion, a dabbler. Johann Simon Mayr (1763–1845) may have been right in observing that “genius does not exist in nature”—and Mozart, even as a wunderkind, is no exception.

You May Also Like

The Violin Concertos: Mozart’s Borrowed Genius

Mozart’s violin concertos are often celebrated as masterpieces, but how much of the music is truly his? This article delves into the complexities behind the compositions and challenges the authenticity of some of his most famous works, revealing a story of influence, imitation, and misattribution.

#2 The Hidden Truth of Mozart’s Education

In this video, we uncover the hidden truth behind Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s early education and challenge the long-held belief in his effortless genius. While history often celebrates Mozart as a child prodigy, effortlessly composing music from a young age, the reality is far more complex.

The London Notebook

The London Notebook exposes the limitations of young Mozart’s compositional skills and questions the myth of his early genius. His simplistic pieces, fraught with errors, reveal a child still grappling with fundamental musical concepts.

The Mozart Question

In this revealing interview, we delve into the lesser-known aspects of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s life, challenging the long-standing myth of his genius. A Swedish journalist explores how Mozart’s legacy has been shaped and manipulated over time, shedding light on the crucial role played by his father, Leopold, in crafting the career of the famed composer.

Georg Nissen and the Missing Notebooks

After Mozart's death, his widow, Constanze, found a steadfast partner in Georg Nikolaus von Nissen, a Danish diplomat who dedicated his life to preserving the composer's legacy. Nissen not only compiled an extensive biography of Mozart but also uncovered and...

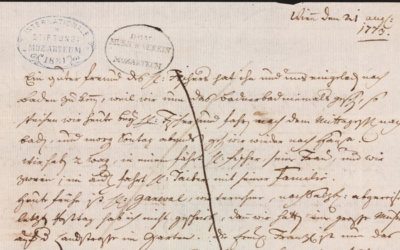

Letters Under Surveillance

In a world without privacy, Leopold Mozart’s letters were carefully crafted not just to inform but to manipulate perceptions. His correspondence reveals a calculated effort to elevate his family’s status while avoiding any mention of failure or controversy.