The Myth of Mozart’s Sight-Reading Genius

A Closer Examination

In the 18th century, exaggerated accounts of Mozart’s abilities were as common as they were fantastical. Yet, detailed reports from figures like Daines Barrington and André Grétry reveal a far more human side of the prodigy, whose skills, impressive though they were, did not amount to the miraculous feats often attributed to him.

Mozart: The Fall of the Gods

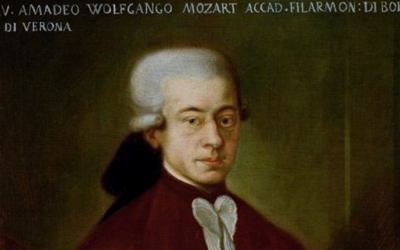

This book offers a fresh and critical look at the life of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, challenging the myths that have surrounded him for centuries. We strip away the romanticised image of the “natural genius” and delve into the contradictions within Mozart’s extensive biographies. Backed by nearly 2,000 meticulously sourced citations, this work invites readers to explore a deeper, more complex understanding of Mozart. Perfect for those who wish to question the traditional narrative, this biography is a must-read for serious music lovers and historians.

"Even the most lauded prodigies sometimes hide a kernel of reality beneath layers of myth."

Mozart: The Fall of the Gods

Separating Fact from Fiction in 18th-Century Reports

In the concert posters promoting young Wolfgang Mozart, he was lauded as a prodigy capable of sight-reading even the most difficult pieces flawlessly. Such claims, often more fantastical than credible, warrant closer scrutiny. Two notable contemporary accounts diverge from the usual paternal praise or the laudatory articles seen in 18th-century newspapers. One is a scientific report from London, penned by Daines Barrington (1727–1800), a member of the Royal Society. The report, dating from June 1765, was finalized in 1769 and presented on February 15, 1770, a full five years after the original test.

Barrington was a multifaceted figure: a barrister, antiquarian, and naturalist with a penchant for ornithology and a fascination for musical prodigies. His book, a curious collection of studies ranging from the origins of turkeys to the melodiousness of birds, often employed flowery and exaggerated language. Perhaps Barrington’s fondness for child prodigies contributed to the surge in popularity of such marvels in England. He documented not only the Mozarts but also other youthful musicians like the Wesley brothers and William Crotch. Yet, his approach lacked scientific rigour, often relying on hearsay and questionable sources.

Barrington’s report on Mozart was no exception. In his experiment, he presented a manuscript duet, its composer unspecified, to test Mozart’s sight-reading skills. The piece was from Metastasio’s Demofoonte, arranged for two vocal parts and strings. Curiously, the vocal parts were written in the alto clef, which Barrington highlighted as if it were a major obstacle. Despite this build-up, Wolfgang executed the symphony introduction “masterfully,” as Barrington put it, then sang the upper vocal line while his father Leopold tackled the lower. Leopold faltered, eliciting disapproving looks from his son, who even corrected his mistakes. Barrington claimed that Wolfgang not only sang beautifully but also embellished the accompaniment with violin parts to enhance the musical effect.

A closer analysis reveals that the test was calibrated for both Mozarts, and Wolfgang, not surprisingly, outperformed his father. Stripping away the superlatives, we see that Wolfgang competently played the bass line with his left hand and added occasional violin parts with his right. Impressive for an eight-year-old, certainly, but not the miracle Barrington made it out to be. His comparison of the duet’s difficulty to reading ancient texts like Etruscan and Greek reveals his musical naivety. Instead of a supernatural feat, the performance was a well-practiced skill honed by Leopold to impress the general public.

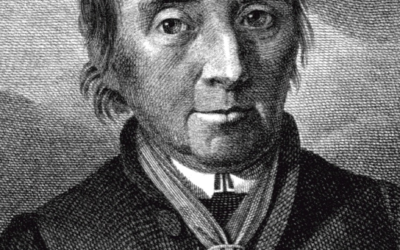

Even more telling is a different account from André Ernest Modeste Grétry (1741–1813), a professional musician who tested Mozart in Geneva. When Leopold boasted of his son’s sight-reading prowess, Grétry composed a challenging sonata movement in B-flat major. Mozart played it, yet replaced several difficult passages with his own improvisations. The audience, except Grétry, was in awe. Grétry’s skepticism highlighted Wolfgang’s reliance on improvisation and lack of systematic study, a strategy that gave the illusion of mastery.

Mozart’s ability to read music, while exceptional for his age, fell short of true sight-reading as it’s defined today: a flawless, spontaneous execution of written music, requiring years of rigorous training and experience. Grétry’s observations dispel the myth of Mozart’s innate genius, pointing instead to his reliance on quick-thinking and a boldness typical of children.

You May Also Like

The Violin Concertos: Mozart’s Borrowed Genius

Mozart’s violin concertos are often celebrated as masterpieces, but how much of the music is truly his? This article delves into the complexities behind the compositions and challenges the authenticity of some of his most famous works, revealing a story of influence, imitation, and misattribution.

#2 The Hidden Truth of Mozart’s Education

In this video, we uncover the hidden truth behind Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s early education and challenge the long-held belief in his effortless genius. While history often celebrates Mozart as a child prodigy, effortlessly composing music from a young age, the reality is far more complex.

The London Notebook

The London Notebook exposes the limitations of young Mozart’s compositional skills and questions the myth of his early genius. His simplistic pieces, fraught with errors, reveal a child still grappling with fundamental musical concepts.

The Mozart Question

In this revealing interview, we delve into the lesser-known aspects of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s life, challenging the long-standing myth of his genius. A Swedish journalist explores how Mozart’s legacy has been shaped and manipulated over time, shedding light on the crucial role played by his father, Leopold, in crafting the career of the famed composer.

Georg Nissen and the Missing Notebooks

After Mozart's death, his widow, Constanze, found a steadfast partner in Georg Nikolaus von Nissen, a Danish diplomat who dedicated his life to preserving the composer's legacy. Nissen not only compiled an extensive biography of Mozart but also uncovered and...

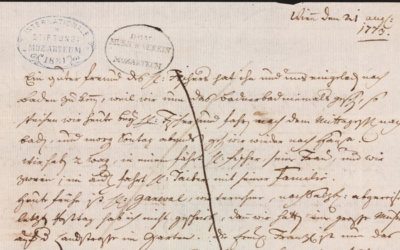

Letters Under Surveillance

In a world without privacy, Leopold Mozart’s letters were carefully crafted not just to inform but to manipulate perceptions. His correspondence reveals a calculated effort to elevate his family’s status while avoiding any mention of failure or controversy.