Tracing the Ideological Roots of the "Viennese School"

and Its Persistent Influence

Far from being a “Viennese classic,” Mozart’s roots and reputation were molded by a network of German musicians and an imperial court bent on monopolizing cultural narratives.

The so-called “Viennese School” was never an organic musical tradition but a label crafted to align music with the political ambitions of the Habsburgs and, later, nationalist ideologies.

Mozart: The Fall of the Gods

This book compiles the results of our studies on 18th-century music and Mozart, who has been revered for over two centuries as a deity. We dismantle the baseless cult of Mozart and strip away the clichés that falsely present him as a natural genius, revealing the contradictions in conventional biographies. In this work, divided into two parts, we identify and critically analyze several contradictory points in the vast Mozart bibliography. Each of the nearly 2,000 citations is meticulously sourced, allowing readers to verify the findings. This critical biography of Mozart emerges from these premises, addressing the numerous doubts raised by researchers.

"The ‘Viennese Classicism’ was no school but a convenient label—one crafted to advance imperial interests and later twisted to satisfy nationalist agendas."

Mozart: The Fall of the Gods

Mozart, like Joseph Haydn and Ludwig van Beethoven, was not truly “Viennese.” As Hermann Abert points out, Mozart’s German heritage—his father hailing from Swabia and his mother from Baden—set him apart from the label that historians have ascribed to him. Unlike Johann Sebastian Bach, whose lineage extended over multiple generations of musicians, Mozart’s Germanic identity was rooted in just a single generation, an ancestry that later proved to be a convenient piece in the puzzle of an Austrian-German musical narrative.

This narrative flourished under the influence of nationalist ideals that persisted even after the fall of Hitler’s regime. During the post-war era, musicologists, many influenced by Guido Adler’s musicology and ideological biases, pushed the idea of a “First Viennese School” (Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven) to which they attached a “Second Viennese School” (Schoenberg, Berg, Webern) as if continuing a lineage of “Viennese” greatness. Ironically, Schoenberg, the Jewish composer who fled Vienna to escape Nazi persecution, was posthumously dubbed part of this “classical” Viennese legacy—an insult to history if there ever was one.

In reality, the concept of a “Viennese Classicism” was hardly even acknowledged during Mozart’s lifetime. His music was not favored at the Habsburg court: Empress Maria Theresa dismissed him as a “beggar,” and Leopold I of Tuscany flatly denied him a composer’s position. Even his celebrated opera The Abduction from the Seraglio, the only one premiered in Vienna, was received as a mere German Singspiel, markedly inferior to the Italian gems gracing the Viennese stage. Among Vienna’s high society, Mozart never ranked alongside Italian opera composers, whose music was deemed the true art of the empire.

Emperor Joseph II, revered as the quintessential Viennese ruler, never included music by Haydn or Mozart in his private collection. Indeed, his court’s music culture reveals a striking absence of these so-called Viennese masters. It wasn’t a matter of style but of power: the Habsburgs employed music as a tool to assert imperial control, with “Viennese Classicism” as a posthumous construct serving nationalist interests.

After the war, this myth extended further, even incorporating Beethoven—a composer with no connection to Vienna’s political elite—as the “proto-Nazi musician.” Far from the image of the revolutionary democrat, Beethoven was cast by Nazi propagandists as a Führer-like figure, leading with heroic will and commanding spiritual authority through his music.

In truth, Habsburg Austria exerted control over its music industry as rigorously as it did over all forms of communication, treating music as a medium to secure public loyalty. The monarchy, governing “with the lyre and the sword,” viewed culture as a political asset. Under this regime, writers like Niccolò Tommaseo faced censorship or exile, as even literary and musical works fell under heavy scrutiny. For Italians, especially, opera was the last refuge for expressing national sentiment under the watchful eye of the empire.

In such an environment, any authentic Italian tradition was smothered by a campaign of regime-backed journalism extolling the supremacy of the Viennese trinity—Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. Newspapers sang the praises of this trio, with fabricated anecdotes and staged portrayals that promoted their image as untouchable “semi-gods,” forever superior to all others. This was not a celebration of genuine heritage but a calculated effort to assert cultural dominance over the music of other nations and silence their voices.

You May Also Like

The Violin Concertos: Mozart’s Borrowed Genius

Mozart’s violin concertos are often celebrated as masterpieces, but how much of the music is truly his? This article delves into the complexities behind the compositions and challenges the authenticity of some of his most famous works, revealing a story of influence, imitation, and misattribution.

#2 The Hidden Truth of Mozart’s Education

In this video, we uncover the hidden truth behind Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s early education and challenge the long-held belief in his effortless genius. While history often celebrates Mozart as a child prodigy, effortlessly composing music from a young age, the reality is far more complex.

The London Notebook

The London Notebook exposes the limitations of young Mozart’s compositional skills and questions the myth of his early genius. His simplistic pieces, fraught with errors, reveal a child still grappling with fundamental musical concepts.

The Mozart Question

In this revealing interview, we delve into the lesser-known aspects of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s life, challenging the long-standing myth of his genius. A Swedish journalist explores how Mozart’s legacy has been shaped and manipulated over time, shedding light on the crucial role played by his father, Leopold, in crafting the career of the famed composer.

Georg Nissen and the Missing Notebooks

After Mozart's death, his widow, Constanze, found a steadfast partner in Georg Nikolaus von Nissen, a Danish diplomat who dedicated his life to preserving the composer's legacy. Nissen not only compiled an extensive biography of Mozart but also uncovered and...

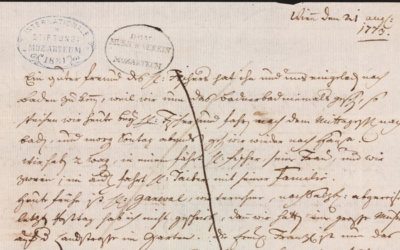

Letters Under Surveillance

In a world without privacy, Leopold Mozart’s letters were carefully crafted not just to inform but to manipulate perceptions. His correspondence reveals a calculated effort to elevate his family’s status while avoiding any mention of failure or controversy.