Wolfgang Amadé Mozart

Unveiling the Myth: The Other Side of Mozart’s Legacy

Explore the untold story of Mozart, where myth and reality collide. Our critical examination of his life and works reveals a legacy shaped by profit, myth-making, and misattribution. Join us in uncovering the truth behind the man and his music.

Mozart The Construction of a Genius: The Untold Story

Mozart: The Construction of a Genius” uncovers how the myth of Mozart was crafted after his death in 1791, initially to support his widow, then exploited by publishers, and later used to elevate Mozart as a cultural icon. Bianchini and Trombetta reveal that the personal catalogue attributed to Mozart is a late 18th-century fabrication, challenging long-held beliefs about his legacy.

“Publishers fail to grasp this simple notion: one cannot publish posthumously! Yet, with Mozart, they have crafted a legacy of misattributed works that overshadows the truth of his modest output during his lifetime.”

Mozart The Construction of a Genius

In the grand narrative of Western classical music, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart is often enshrined as a towering genius, his compositions celebrated as masterpieces. However, there exists a lesser-known perspective—one that challenges the conventional reverence for Mozart and questions the authenticity of the legacy attributed to him. On our website, Mozartrazom, we delve into this alternative narrative, presenting Mozart in a light far removed from the traditional glorification.

The Questionable Attribution of Works

One of the most striking aspects of Mozart’s posthumous reputation is the sheer number of compositions attributed to him after his death. During his lifetime, Mozart was known to have published only 144 compositions. Yet today, the official catalogue lists a staggering 626 works under his name, including the famous Requiem. This discrepancy raises serious questions about the authenticity of many pieces now attributed to Mozart, suggesting that publishers and promoters, motivated by profit, may have ascribed to him works that he never composed.

The Case of the Quintet for Harpsichord and Wind Instruments, K. 452

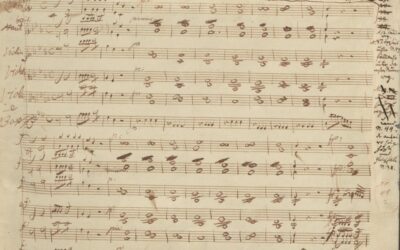

A closer examination of specific pieces attributed to Mozart further illuminates these doubts. Take, for instance, the Quintet for Harpsichord and Wind Instruments, K. 452. Despite being lauded by Mozart himself in his correspondence as one of his finest works, this piece bears no name, date, or location on its manuscript—details typically crucial for verifying authorship. Furthermore, this quintet was only published three years after Mozart’s death, and not as a quintet, but as a quartet for piano and strings, a significant alteration that raises questions about its original intent and authenticity.

The Creation of a Myth

The myth of Mozart as an infallible musical genius was not formed overnight but was the result of a calculated and gradual process, spanning several decades. It began with the proliferation of anecdotes and biographies, many of which exaggerated or romanticised Mozart’s life and talents. This was followed by the systematic publication of his compositions and the creation of a comprehensive catalogue, which included works that were heavily edited or even misattributed. Over time, this process has led to the enshrinement of a version of Mozart that bears little resemblance to the reality of his life and work.

The Role of Constanze Mozart in Shaping the Legacy

After Mozart’s death, his widow Constanze found herself in a difficult financial situation, burdened with debt and the responsibility of raising two young children. In response, she took an active role in shaping and promoting Mozart’s legacy, sometimes resorting to embellishments and fabrications to secure a steady income from his music. A notable example is her dedication in the Mozart guest book, which, while appearing to be a heartfelt tribute written shortly after Mozart’s death, was actually penned years earlier on a page commemorating a different event.

Constanze’s efforts to control Mozart’s legacy extended to purchasing copies of Schlichtegroll’s 1793 Obituary, which offered an unflattering portrayal of Mozart and highlighted his financial irresponsibility and personal flaws. By buying out 600 copies, Constanze attempted to suppress this version of Mozart’s life, ensuring that the more favourable, profitable image she had helped cultivate remained dominant.

The Requiem: A Controversial Masterpiece

Perhaps the most famous piece associated with Mozart is the Requiem, a composition that has been surrounded by myths and legends since its completion. Despite its status as one of Mozart’s greatest works, the Requiem was left unfinished at the time of his death. The version we know today was completed by his student, Franz Xaver Süssmayr, who went so far as to inscribe the date ‘1792’ on the manuscript, a full year after Mozart had passed away. This blatant manipulation underscores the extent to which Mozart’s legacy has been crafted, rather than purely inherited.

You May Also Like

The Legend of Mozart’s Miserere

The enduring popularity of the narrative surrounding Mozart’s Miserere highlights the allure of the prodigy myth, but as we peel back the layers, we uncover a more nuanced picture of his life and the musical landscape of the time. The reality often contrasts sharply with the romanticized tales that have shaped our understanding of his genius.

Rediscovering Musical Roots: The World Premiere of Gasparini and Mysliveček

This December, history will come alive as the Camerata Rousseau unveils forgotten treasures by Quirino Gasparini and Josef Mysliveček. These premieres not only celebrate their artistry but also reveal the untold influence of Gasparini on Mozart’s Mitridate re di Ponto. A pivotal event for anyone passionate about rediscovering music history.

The Curious Case of Mozart’s Phantom Sonata

In a striking case of artistic misattribution, the Musikwissenschaft has rediscovered Mozart through a portrait, attributing a dubious composition to him based solely on a score’s presence. One has to wonder: is this music really Mozart’s, or just a figment of our collective imagination?

The Illusion of Canonic Mastery

This post explores the simplistic nature of Mozart’s Kyrie K.89, revealing the truth behind his early canonic compositions and their implications on his perceived genius.

The Unveiling of Symphony K.16

The Symphony No. 1 in E-flat major, K.16, attributed to young Wolfgang Mozart, reveals the complex truth behind his early compositions. Far from the prodigious work of an eight-year-old, it is instead a product of substantial parental intervention and musical simplification.

The Cibavit eos and Mozart’s Deceptive Legacy

The Cibavit eos serves as a striking reminder that Mozart’s legacy may be built on shaky foundations, questioning the very essence of his so-called genius.