The Influence of Ligniville

Unpacking Mozart's Early Education

The story of Ligniville illustrates the pitfalls of romanticizing Mozart’s early life and education, reminding us that the narrative of genius is often a construct that obscures the laborious aspects of musical development.

Mozart: The Fall of the Gods

This book offers a fresh and critical look at the life of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, challenging the myths that have surrounded him for centuries. We strip away the romanticised image of the “natural genius” and delve into the contradictions within Mozart’s extensive biographies. Backed by nearly 2,000 meticulously sourced citations, this work invites readers to explore a deeper, more complex understanding of Mozart. Perfect for those who wish to question the traditional narrative, this biography is a must-read for serious music lovers and historians.

"Don’t put strange ideas in her head. She plays like grass grows; it’s her nature: she is not a prodigy."

Mozart: The Fall of the Gods

“Don’t put strange ideas in her head. She plays like grass grows; it’s her nature: she is not a prodigy. If she hears these words, she will get an inflated sense of self, imagining some magnificent future, whereas it will always be work and more work.” This quote encapsulates the skepticism surrounding the notion of child prodigies in the context of musical education, particularly when we examine Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s formative years.

The idea that Mozart was a genius who mastered the intricacies of composition at an early age has been championed by figures like Abert, who suggested that Wolfgang learned the rules of writing from Maestro Martini. However, recent musicological research has dismantled this theory, revealing the complex truth about Mozart’s early education and the roles of those who influenced him, including the Marquis de Ligniville.

Leopold Mozart, Wolfgang’s father, regarded Ligniville as “the best contrapuntist in all of Italy.” Ligniville, a member of the prestigious Accademia Filarmonica in Bologna, was thought to represent the old Roman school of counterpoint. It was under his influence that Mozart supposedly composed significant works, including the Stabat Mater K.Anh.17 and the Kyrie K.89. For decades, these attributions went unchallenged, reinforcing the myth of a young Mozart capable of complex contrapuntal writing.

Yet, as modern scholars now assert, many of these pieces were actually copied by Mozart, leading to a reevaluation of his abilities as a contrapuntist. The lingering perception that Mozart excelled in counterpoint persists in numerous academic texts, despite the lack of substantiated evidence. It is striking how musicology, which should shun dogma, continues to propagate such myths, comparing Mozart’s work to that of other composers like Haydn and Rossini.

In particular, the Stabat Mater has garnered attention for its apparent mastery of canonic writing. Contemporary biographers marveled at a young boy’s ability to control compositions reminiscent of late 16th-century styles. However, we now recognize that the piece was heavily influenced by Ligniville’s work, with only a fraction of the movements authentically attributed to Mozart. Indeed, it has been established that Wolfgang copied Ligniville’s Stabat Mater, which itself consisted of straightforward canons, devoid of the sophisticated depth characteristic of true counterpoint.

Notably, Ligniville’s reputation as a composer was not grounded in his ability to write intricate fugues. His music—often simple and lacking the rigor required for upper-level composition courses—failed to impress contemporaries, including Grand Duke Pietro Leopoldo, who noted the work as “singulier” rather than “excellent.” This implies that while Ligniville may have held some esteem, he did not possess the skills that would warrant the title of the greatest contrapuntist in Italy.

Leopold’s enthusiasm for Ligniville’s abilities raises questions about his own understanding of counterpoint, revealing that he may have misjudged the Marquis’s capabilities. While Ligniville did have some influence on Mozart, it appears to have been limited and heavily reliant on copying rather than original composition. This oversight contributes to the enduring misconception of Mozart’s innate genius, overshadowed by the more mundane realities of musical training and imitation.

Ultimately, the story of Ligniville illustrates the pitfalls of romanticizing Mozart’s early life and education. It serves as a reminder that the narrative of genius is often a construct, one that can obscure the more laborious and collaborative aspects of musical development.

As we continue to explore the complexities of Mozart’s influences, it becomes increasingly clear that his path was marked by learning, imitation, and the guidance of those who came before him, rather than a straightforward ascent to greatness.

You May Also Like

The Violin Concertos: Mozart’s Borrowed Genius

Mozart’s violin concertos are often celebrated as masterpieces, but how much of the music is truly his? This article delves into the complexities behind the compositions and challenges the authenticity of some of his most famous works, revealing a story of influence, imitation, and misattribution.

#2 The Hidden Truth of Mozart’s Education

In this video, we uncover the hidden truth behind Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s early education and challenge the long-held belief in his effortless genius. While history often celebrates Mozart as a child prodigy, effortlessly composing music from a young age, the reality is far more complex.

The London Notebook

The London Notebook exposes the limitations of young Mozart’s compositional skills and questions the myth of his early genius. His simplistic pieces, fraught with errors, reveal a child still grappling with fundamental musical concepts.

The Mozart Question

In this revealing interview, we delve into the lesser-known aspects of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s life, challenging the long-standing myth of his genius. A Swedish journalist explores how Mozart’s legacy has been shaped and manipulated over time, shedding light on the crucial role played by his father, Leopold, in crafting the career of the famed composer.

Georg Nissen and the Missing Notebooks

After Mozart's death, his widow, Constanze, found a steadfast partner in Georg Nikolaus von Nissen, a Danish diplomat who dedicated his life to preserving the composer's legacy. Nissen not only compiled an extensive biography of Mozart but also uncovered and...

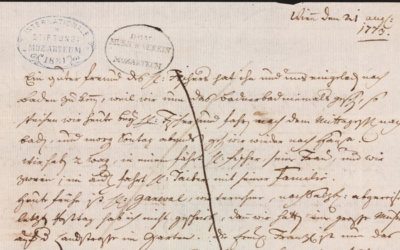

Letters Under Surveillance

In a world without privacy, Leopold Mozart’s letters were carefully crafted not just to inform but to manipulate perceptions. His correspondence reveals a calculated effort to elevate his family’s status while avoiding any mention of failure or controversy.